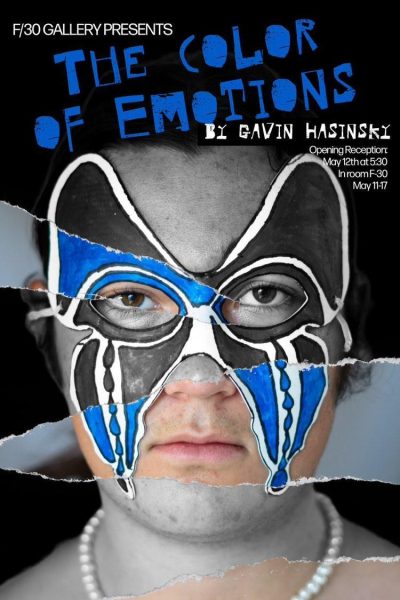

During the spring of 2020, many people stuck inside their homes took isolation as a chance to reflect on themselves. Some people turned to hobbies, others decided to travel across the states, and then some chose to look closer at their emotions to see if there was something more to what they were feeling. Chloe Saye fell into the last group.

Saye, a 23-year theater student at Palomar College, decided to do some research after feeling confused and frustrated with her mental health. She noticed she tended to get more upset with rejection than her peers, whether that was rejection during an argument with a sibling as a child or her first breakup during her teens. She questioned her self-worth and wanted to know if there was more to these emotions.

Saye talked to her friends diagnosed with ADHD and autism and began to see similar symptoms and experiences between herself and those friends. She even took multiple online assessments, like the Adult Self-Report Scale (ASSR), which helps people identify the symptoms of ADHD. After putting all of these resources together, she felt confident to say that she had ADHD.

Chloe Saye had self-diagnosed.

Self-diagnosing is when people diagnose or identify medical conditions by themselves. They usually research the symptoms they are experiencing online. Those concerned about their health may research minor things, such as why they have headaches. Others may do more in-depth research on their mental health symptoms.

Self-diagnosing has been a growing trend on social media since 2020. Aleksandria Grabow, an assistant professor at Cal State San Marcos, specializes in the effects of social media on mental health and credits apps like TikTok for the rise in such a trend. These social media accounts have given teens and young adults a safe space to examine their mental health.

“I tend to notice that the younger generation, also the generation who tends to utilize social media more, are the ones who tend to cite a self-diagnosis at higher rates than other folks in the community,” Grabow said.

She also noted that education could impact the rise of self-diagnosing. Students attend psychology classes in high school and college, allowing them to understand their own experiences better. She also suggests that it’s hard not to self-diagnose when looking at learning resources like the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

A high school psychology class led Alcyone O’Marrie, a 20-year-old Colorado State University student, to research her mental health experiences. Her family didn’t discuss mental health, which led her to keep it secret. It wasn’t until this class that she understood what she was going through. “At the time, I needed to have a word that would define what was going on with my head,” O’Marrie said. “I thought it was just a combination of stress and anxiety. But I just needed a word to define it so that I’d be able to say, ‘There’s a reason for this.’”

The need to define their experiences or symptoms leads most to self-diagnose. Like Saye, O’Marrie used a combination of stories on social media, online resources, and assessments to understand her mental health better. These resources can provide validation for those who may not be able to see a professional due to the stigma surrounding mental health within their family.

“Because there was such a stigma within my family… I didn’t have anyone that I could be like, ‘Hey, is this normal?’” O’Marrie said. “I just had to go on what I found online and what I have lived through.”

Cultural and familial beliefs are another factor that can lead someone to self-diagnosing. Cal State San Marcos Professor, Gerardo Gonzalez, has studied multicultural mental health issues and explained that the culture we are raised in impacts how we view our mental health. “Stigma is linked to culture because some traditional cultures are less likely to discuss mental health openly,” Gonzalez said. “Also, some communities may view the origins of mental health concerns based on traditional or family understanding, which may not necessarily be a scientific perspective.”

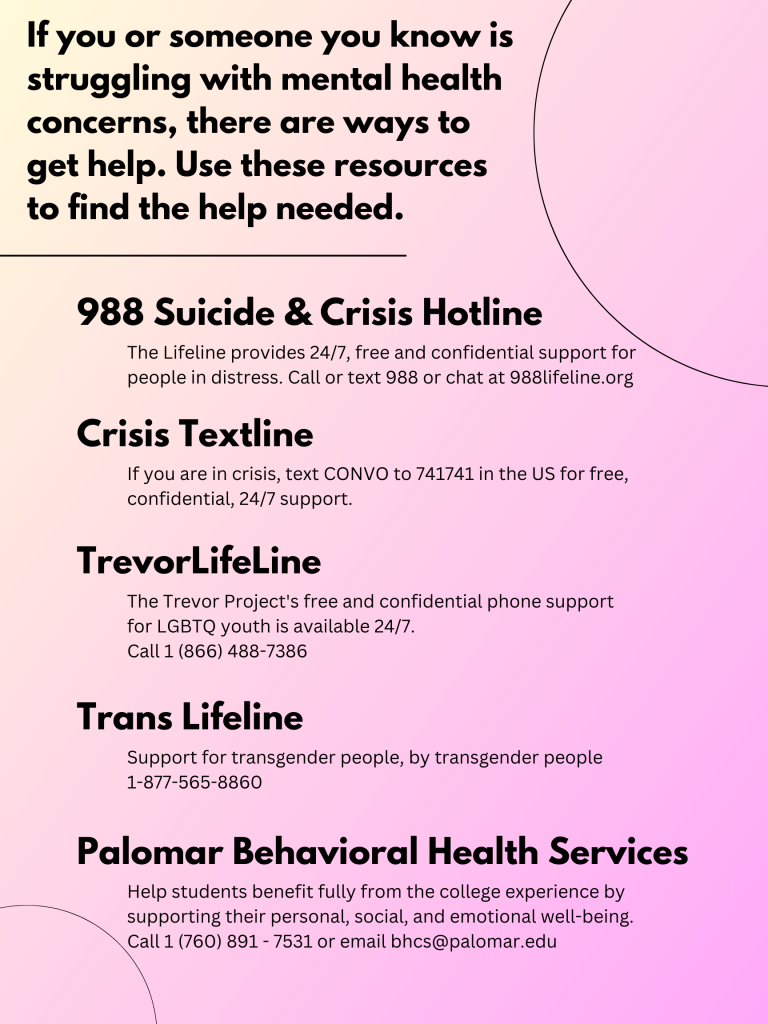

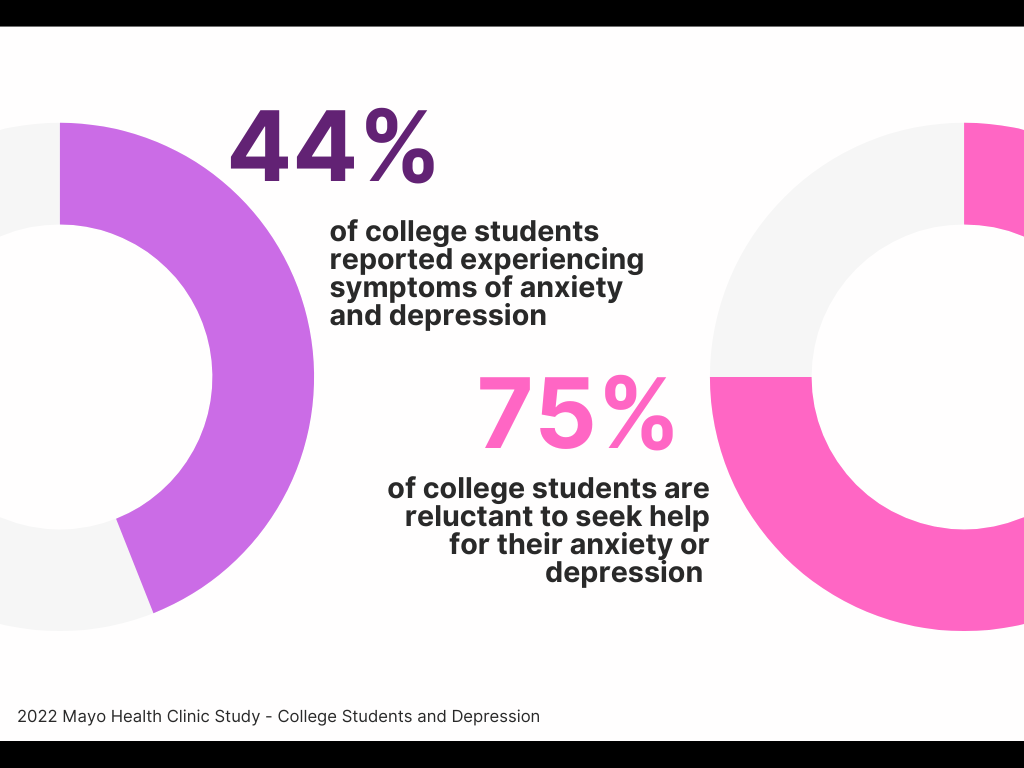

The high cost of therapy is another reason some choose to self-diagnose. The average price to see a therapist ranges from $75 to $200 per visit, which can be a lot of money for a college student on a limited income. And even services like BetterHealth, which offer virtual therapy sessions, can cost a lot based on how often you use the service.

Grabow said that the mental health industry is a flawed system. Expensive visits that drain bank accounts and long wait lists are some of the barriers many people face. However, climbing these barriers can be worth it if someone is motivated enough to get help.

“I hear that frustration. It’s hard to connect with a professional a lot of times,” Grabow said. “But I do think the more folks that know that this is something they want, the more we can connect with you. Because for folks in the mental health field, we absolutely want you to feel healed and connected.”

With so many barriers, it is easy to understand why some people self-diagnose. However, Grabow and Gonzalez address the risks of choosing to do so. “I think self-diagnosing can be empowering, and it can also be debilitating. It depends on the person,” Grabow said. “There’s no one-size-fits-all model to say whether it’s right or wrong for every single person.”

Diagnosing a mental illness isn’t easy, said Grabow and Gonzalez; it takes time and a lot of information. The DSM isn’t simple, and someone’s symptoms could be found under multiple diagnoses, which could lead to a misdiagnosis. “There are implications to diagnosing, for better or worse,” Grabow said. “It can have long-term effects. Someone who might have that training is able to see the bigger picture of what it means to diagnose someone with (something like) post-traumatic stress disorder.”

Another risk of self-diagnosis is not knowing what to do next, which could lead to feeling overwhelmed or helpless. It could also influence someone to internalize their self-diagnosis, amplifying negative thoughts about their condition.

However, Grabow said that there are benefits of self-diagnosis. It can be the first step to better mental health by giving them self-empowerment and a name for their experience.

As a counselor, Grabow encountered many clients with varying levels of self-diagnosis. She advises that patients connect with a profession first, “even just to get through that first assessment.”

“Having self-diagnosis acknowledged by a professional can be super relieving,” Grabow said. “It can be helpful to have another human being there to hear (your symptoms) and process it, versus going to WebMD.”

Saye and O’Marrie both self-diagnosed before seeing a professional. This gave them the resources to understand their symptoms better and the words needed to describe those experiences. They both expressed that getting a second opinion from a professional was validating and gave them even more resources to help themselves.

“I say go for it,” Saye said. “Especially if you want that validation and you want to take that step towards getting an official diagnosis. Gather all the information you’re able to, go to a doctor or psychiatrist, and say, ‘I have all this evidence. I have all these symptoms. Do you think I have this?’”

Self-diagnosing gave Saye the validation she was looking for, and it helped her see her ADHD more positively. “My favorite part about being neurodivergent is the hyper fixations,” she said. “Because when I do have fixations, they take up about 95% of my brain. I need to be consuming media about it at any given time.”

Saye’s hyper-fixation comes off as passion and excitement as she shares her current fixations: the FX series “Legion,” the book series Warrior Cats, and her current Dungeon and Dragons campaign. She also uses these fixations as an idea to create new accessories and jewelry. She crafts together jewelry, keychains, and purses using tiny, colorful beads.

“It’s a good hobby for me to do,” She said. “It keeps my hands busy because I need to be fidgeting 24/7.”

Saye is now taking steps to get a professional diagnosis for her ADHD. A barrier that she is still struggling with is her phone anxiety, which makes it difficult for her to reach out to a professional. But she’s hoping that seeing a therapist and getting the diagnosis will give her even more resources to help herself.

Grabow and Gonzalez also know that therapy isn’t the only option. Hobbies, like Saye’s crafting, are a simple and fun way to practice self-care. And creating a support group and having people to talk with is another excellent way to feel validated in your experiences.

Saye also suggested that better acceptance in schools could benefit students’ mental health struggles. This would include empathetic faculty members, so if someone is struggling with their mental health, they won’t hesitate to talk to someone.

Grabow also suggested more integration between mental health and education in a college setting but also in K-12. She hoped that seeing a change like this would provide a comprehensive education on mental health and reinforce the idea that counseling or therapy can be for smaller life events.

“Just normalizing it,” Grabow suggested. “Talking about it as much as possible in the various social contexts we’re in. The more we talk about it, the more destigmatization happens. And hopefully, it will lead to more folks who want to get into the field because we need more providers, too.” •