Computer science Palomar student challenges gender stereotypes while pursuing her dreams.

There’s an old riddle that goes like this: A father and son get into a horrible car crash. The dad is killed, and the son is rushed to the hospital. Just before the operation, the surgeon says, “I can’t operate—that boy is my son!”

Who is the surgeon?

According to studies, a majority of people struggle to guess this one correctly, but the answer is ridiculously simple: The surgeon is the boy’s mom. This riddle helps to illustrate how the idea of women working in certain STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) still hasn’t been normalized. That’s why many tend to overlook it as a reality of the 21st century.

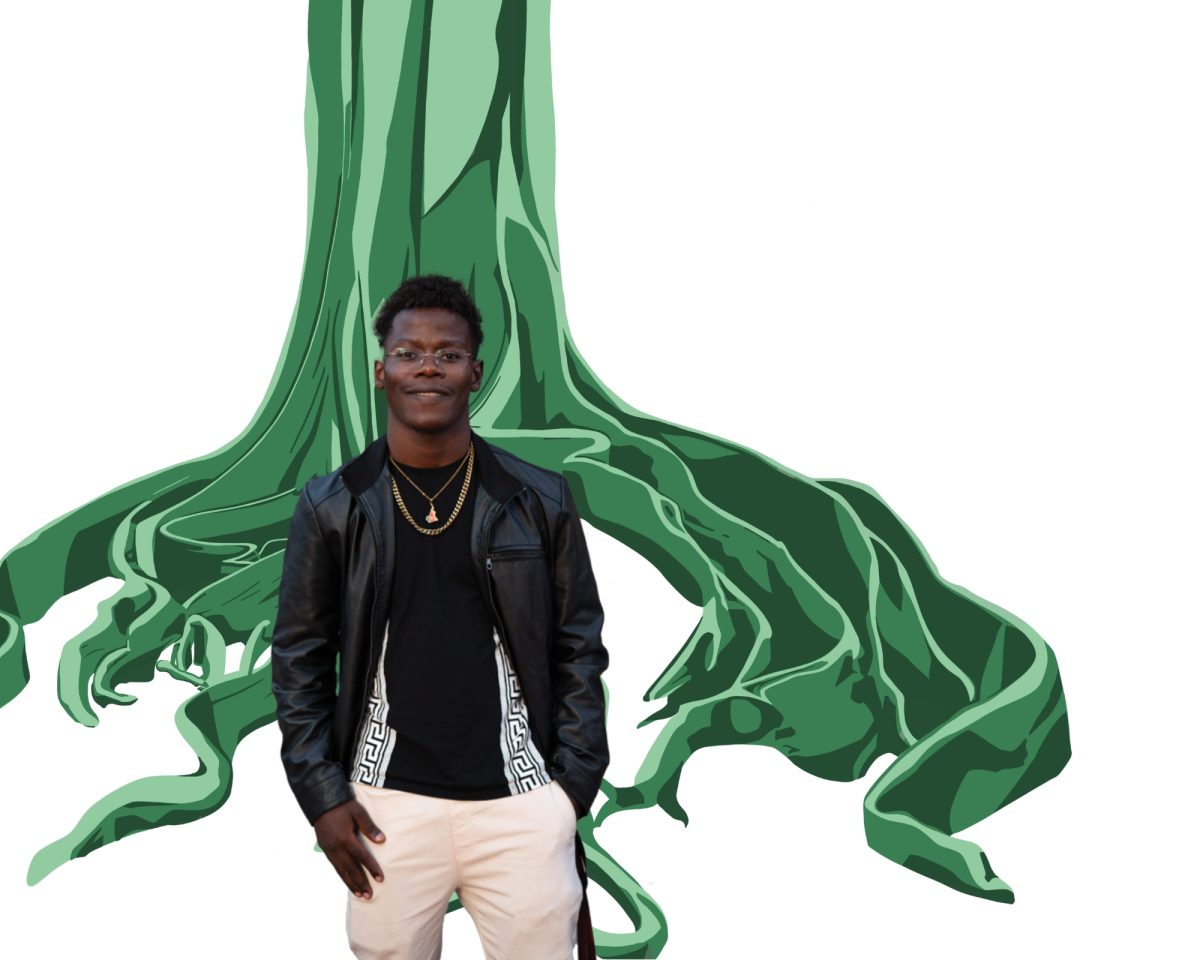

“If you would have told me three years ago, I would have been like ‘I’m doing what?!’” Lindsey Rappaport said, chuckling at the idea, who sat across from me at a picnic table at the campus courtyard. “Because I’ve never coded in my life and now I’m literally working as a programmer.”

Unconscious gender bias is just one feature of a broader issue that’s rooted in our history and is heavily influenced by present-day culture. The persisting gender gap underrepresents women in the STEM workforce, who make up about 28 percent of this population, according to the American Association of University Women.

Rappaport, 18, recently became part of this workforce and is one of about 20 percent of women who are earning their degree in a computer tech field. She kicked off her journey at Palomar College with the help of the school’s STEM program. She is completing her second year at Palomar and is preparing to transfer to UCSD to complete her bachelor’s in computer science. As a member of the STEM Core program, she was given access to tools and resources to help guide her.

“Literally, Palomar, the STEM program—everything here totally just put me in a position that I feel like I would have never been at had I gone somewhere else because I’ve been exposed to so much here,” Rappaport said. The STEM Core program is a one-year accelerated program designed for students who have interest in earning a STEM degree but maybe feel unprepared or unsure of where to start. It provides them with tutoring support, workshops, and networking opportunities to help them be ready to transfer.

“It’s really math-driven,” said Angelique Ehle, the STEM Student Support Specialist at Palomar. “Math is a major hurdle. A major hurdle and a lot of students drop or change their majors, especially when they get to the UC or the CSU because it’s too competitive. It’s too difficult. They didn’t really learn the fundamentals of math. And so the STEM core program gets them prepared.”

Rappaport was referred for a remote internship through the program, at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in Berkeley, Calif. As a graphic design programmer, her role there is to embed images with code that will be used for testing data.

“I’m helping to develop this tool that hasn’t been successfully adapted to this point. When it’s done, which should be soon, it’s going to be used globally by scientists to make new discoveries about different organisms.” Last year, she was hired by the organization, and she continues to work part-time with her studies.

She pointed out that she isn’t really ‘a biology person,’ and told me about her struggles with imposter syndrome. It’s a condition that many people experience, regardless of their skill or experience level. Imposter syndrome is that pesky feeling of self-doubt and uncertainty about whether one is actually qualified enough or ‘fit for the job.’

“Realistically, I’m new to it. I mean, I just started [coding] when I came here, so I’m always like, ‘Hmm, okay, hope I made the right choice here. Like, you know, is it gonna work out? Am I good at this?’ I’m just like, constantly questioning myself.”

Many women and girls are exposed early on to gender stereotypes that suggest that men and boys are naturally more adept in subjects like math or science and that certain jobs are just better suited for men. As a result, female students tend to underperform in math tests due to a lack of confidence, and their interest in these subjects becomes limited, according to the report “Why So Few” published by AAUW.

“It’s challenging but if you study and you’re putting the effort in, you can do it. It’s a lot of work and dedication… I just hate when people say they can’t because they think they’re not smart enough. It’s like, you never know what you can do until you try it.”

However, with so few women working in tech and in other STEM industries, female role models are extremely scarce. “I think it’s discouraging for a lot of women when they feel like they’re alone and they can’t have people to turn to,” said Rappaport. “A lot of women might not feel safe in a male-dominated workplace or environment and I think that holds them back, or they might feel like they need to go for the safe option, or they might feel like they’re not as good as the guy going up against you know, for the position, and it’s really sad.”

Efforts are being made to encourage equality, diversity and inclusion in the workplace. Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, Calif., for example, increased its female graduation rate from 12 to 40 percent in a span of five years. The college made adjustments to its computing courses and brought students to the Grace Hopper Celebration of Women in Computing conference.

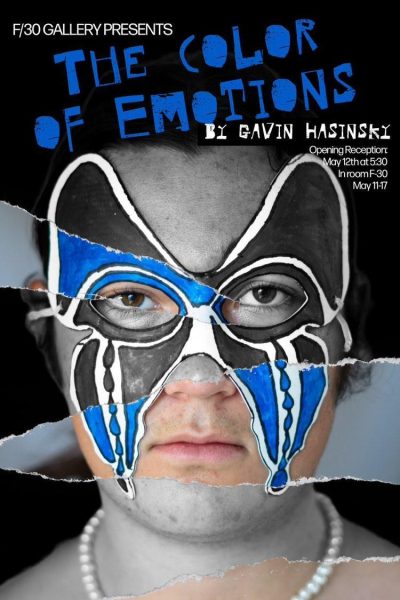

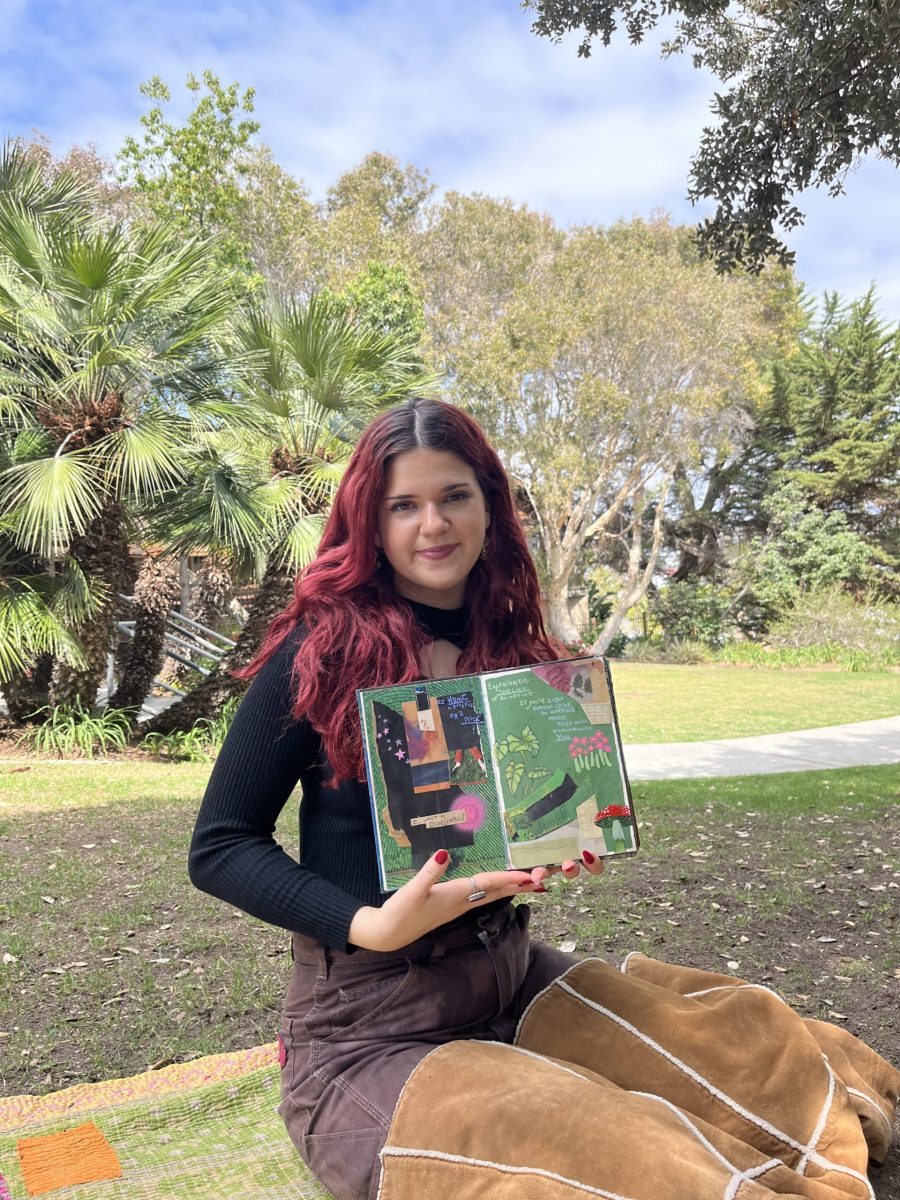

(Photo courtesy of Lindsey Rappaport.)

Women in STEM is a movement that was founded in 2017 at the University of Chicago lab schools. Consisting of 78 chapters around the world and 1,400 members, its mission is to advocate for gender equality in STEM and provide more learning opportunities for young women. The National Girls Collaborative Project is a large network of organizations that are seeking to educate and inspire young women to pursue careers in STEM. It provides tools and resources to strengthen developing programs.

“So how can you advocate for a woman if you’re not aware, right, so just bringing attention to it, you know, and making men our allies and not focusing on what they’re doing wrong but focusing on what they’re doing right and making them our outlets,” says Ehle, who also runs Palomar’s Women in STEM Network in association with the STEM core program. It hosts workshops and guest presentations and gives students a chance to share their experiences with one another.

Outside of work and school, Rappaport is a published musician. She’s been writing music since first grade and has no intentions of stopping. She released her first EP album, “Lost Again” in 2019. “I wrote most of the songs when I was like, 14, so it’s a little funny listening to them now… I was actually supposed to record another one right before COVID hit. And then at this point, now I’m like, I don’t even like those songs anymore because I wrote those years ago.”

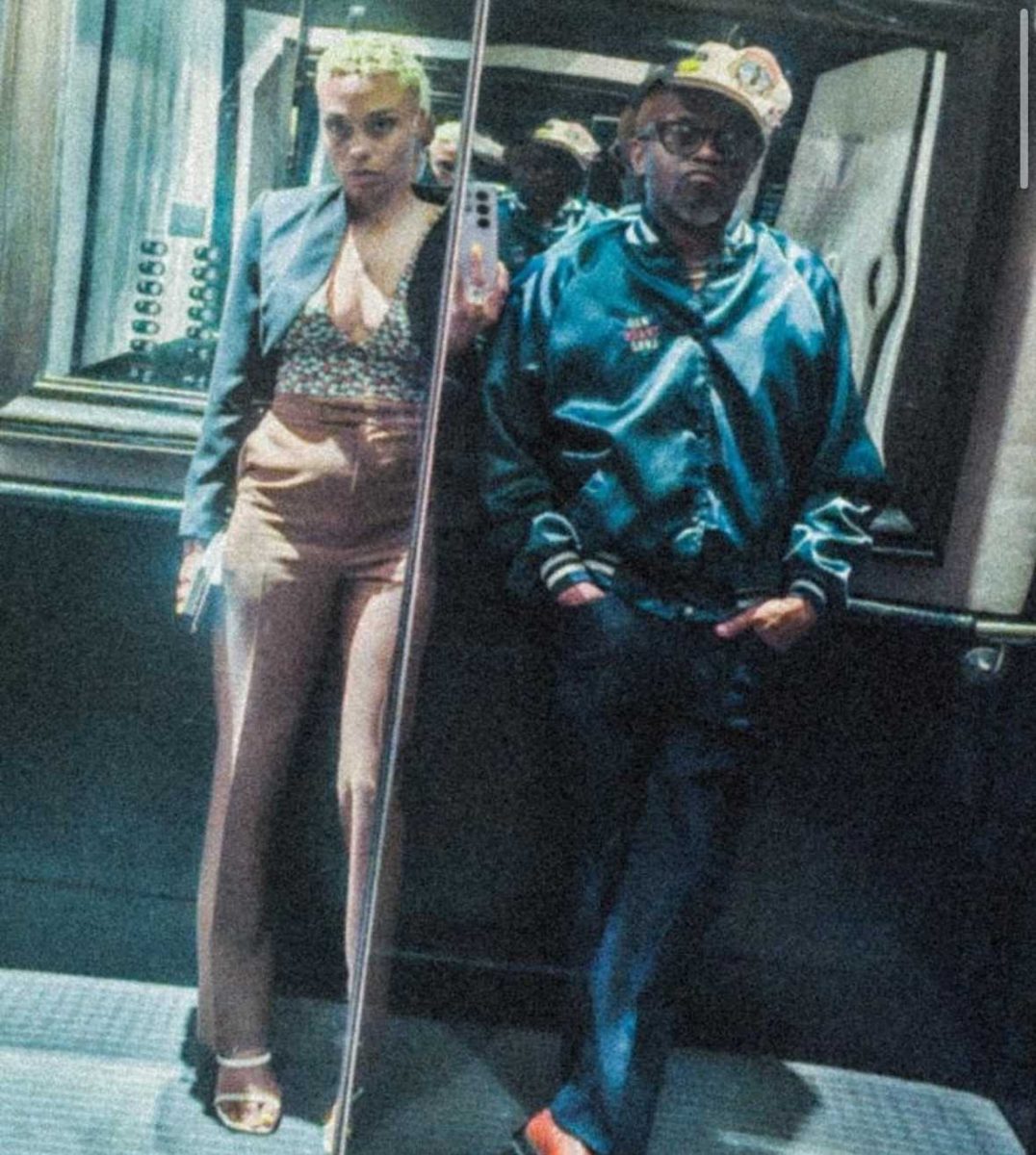

I think that holds them back.” ~ Lindsey Rappaport. (Photo courtesy of Jenn Mohn.)

She hopes to write more music soon, but finding the time is a challenge with her busy schedule. “Specifically last semester, which was the 20-unit semester because I had like zero time and I had to turn down modeling opportunities and music opportunities. And that was really difficult because it’s like, music has been my passion my whole life.”

When I asked about her proudest accomplishments, she let out a big sigh and jokingly replied. “Staying sane.” After reflecting for a moment, she added, “I know I’ve worked really hard in spite of factors that are against me. And I’m proud of continuing and not letting that deter me from the field that I’m in… I’m proud that I have so much on my plate and I’ve managed to be successful in most of them.”

Rappaport plans to do various internships over the summers and explore the different branches of computer science. As a passionate advocate for mental health awareness, she also hopes to build an app for music therapy. “If I can help somebody with music, that’s always been my main goal, just writing about things that matter. And trying to connect to people that way.”