SAN MARCOS – There are currently over 200,000 veterans living in San Diego County, around 60,000 of them are veterans of the Vietnam War. Many still serve their military and Veteran communities to this day.

Throughout the U.S.’s involvement in the Vietnam War, over 2.7 million Americans served in Vietnam with over 350,000 Purple Hearts being awarded. Many of those Veterans that were awarded the Purple Heart are still helping serve the military community today.

There is a number of different organizations that serve Veterans, such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW), the Disabled American Veterans (DAV), the Military Order of the Purple Heart (MOPH), and the American Legion. All these organizations have the goal of providing assistance and resources for veterans as well as advocating for Veterans’ rights and needs in Congress and with the Veterans Administration (VA). Their work has spanned over 100 years of service to Veterans, and they are still going strong today. The organizations are run by Veterans and continue to preserve the bonds made within the military and veteran communities.

The Telescope spoke to some of the Veterans involved in these organizations, who told their stories and experiences.

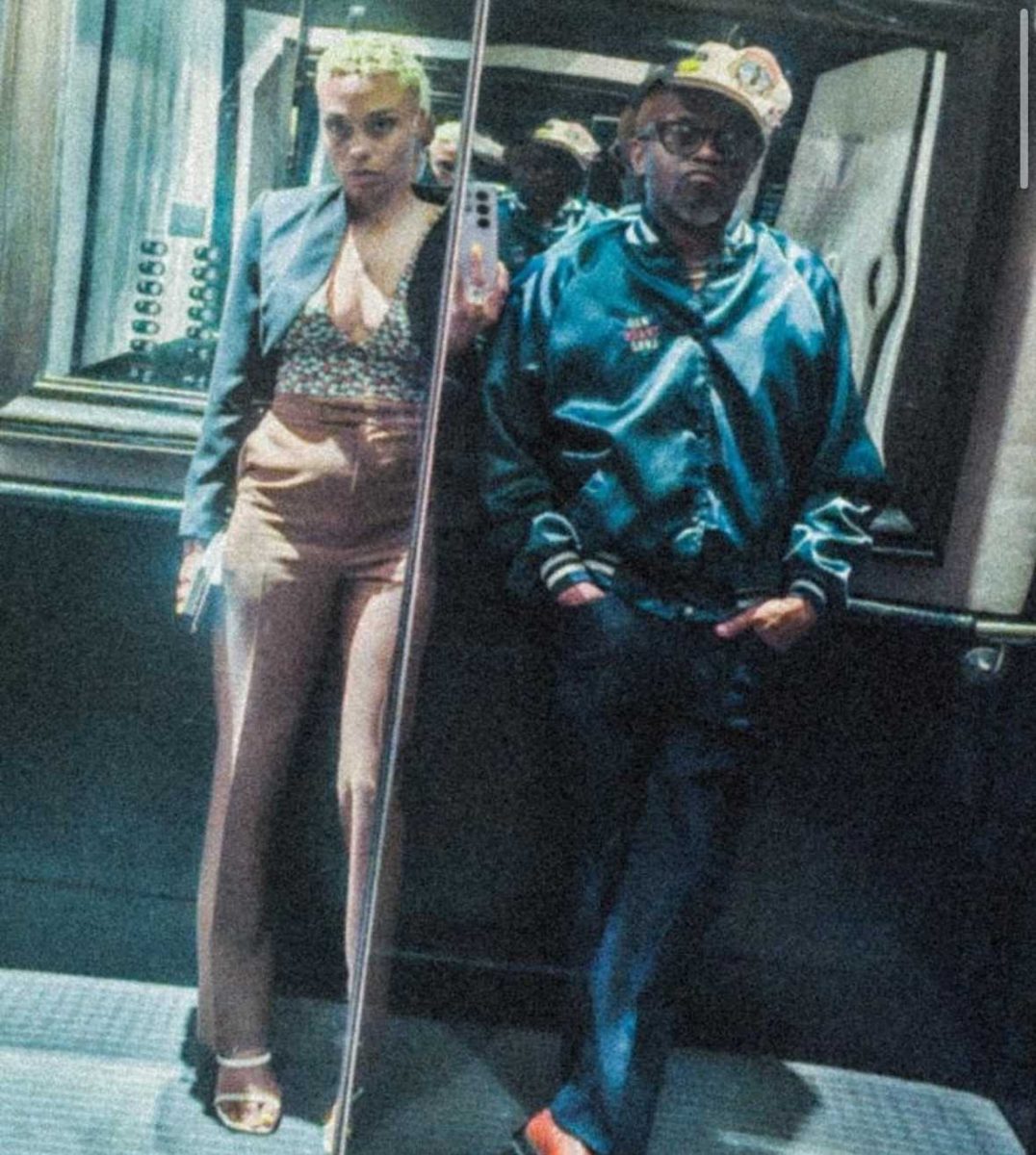

Charles Anderson

Charles Anderson is a Marine Corps veteran who served in Vietnam and was awarded the Purple Heart after being wounded on November 10, 1968, the Marine Corps’ birthday.

“I was inserted into a hostile environment – in other words, a firefight – and I jumped out the helicopter and I led with my chest right into shrapnel from a B40 rocket. And, if that wasn’t bad enough, I was then shot in the leg by an AK-47,” explained Anderson about the day he was wounded. “Up until that day I had no idea it was the Marine Corps’ birthday. In the hospital, some of the doctors really got on me about that and they asked me, ‘How could you possibly get wounded on the Marine Corps birthday?’ And it was quite simple, being in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

There is still shrapnel located inside Anderson’s chest that couldn’t be surgically removed without causing more damage.

“What I remember about getting hit, two things stand out to me. One, there was no pain. And two, I didn’t drop my rifle,” he said recalling when he was wounded. “The concussion from the rocket sent me one way, my helmet went another way, and my gear another. But, for some reason, I held onto my rifle. And I laid there bleeding and thinking about that.” Anderson was sent into battle on a Sunday around 11 am and couldn’t get medically evacuated until the following Monday morning because of the ongoing firefight.

Anderson had enlisted in the Marine Corps with the goal of making a career out of it, however, the shrapnel from that B40 rocket put a stop to his plans. His wound from the shrapnel stretched across from his left shoulder across his chest.

“I joined in 1967 and was wounded in 1968 and it wasn’t until 1970 that I was returned to duty 100%. Since it took so long for my wounds to heal, when it came time for my re–enlistment, I was denied because I was still in rehab for my wounds,” Anderson said on how his plans were changed because of his injury.

Knowing that the extent of his injuries would prevent him from continuing as a Marine, Anderson decided that all he wanted to do was serve the remaining two–and–a–half years of his enlistment contract.

“So, I had gone to the JAG (Judge Advocate General’s Corps of the United States Army), and they wrote a letter to the Commandant of the Marine Corps asking to let me serve all four years of my enlistment. And to my surprise instead of kicking me out right then and there with a medical discharge, I was allowed to finish my four years and I spent the remaining two–and–a–half years stationed at Guantanamo Bay and then Camp Pendleton. That’s how I ended up in San Diego County.”

After leaving the Marine Corps, Charles Anderson took a year off to go and explore California after having not seen much outside of his hometown, Houston, Texas. He then came back to San Diego County and began attending Mira Costa Community College and transferred to the University of San Diego. Anderson graduated from the University of San Diego with a bachelor’s degree in Sociology and worked in the probation department at a juvenile correctional facility. He later left working in probational services to become a welder.

“With only a bachelor’s degree I was already almost tapped out on money, so I became a certified welder. I was hanging off the side of buildings because I really wanted to make as much money as I could and you had to do that kind of shit to make money,” Anderson joked. “But over time it kind of exasperated my respiratory problems because I was already having problems with my lungs and arteries that I didn’t know about yet.”

A major consequence of serving in Vietnam, which many veterans still suffer from, is the illnesses due to exposure to the chemical Agent Orange. After the Vietnam War, many of the people who were exposed to the herbicide would suffer from a multitude of health issues and cancers. The use of Agent Orange in Vietnam also saw an abnormally high rate of reproductive issues and birth defects in descendants of those exposed to it. Charles Anderson was one of those people who would end up suffering from health problems due to his exposure.

“A problem that I had like everyone else that was down there in Vietnam; I was exposed to Agent Orange. I ended up having to get a triple bypass and the VHA (Veterans Health Administration) cardiologist told me that my best artery was only 90% clogged. It was to the point where if I walked from my kitchen to the front door, it would kick my ass,” Anderson began to explain about his health problems.

“I was in Valley Center one day and I got really dizzy so I sat down and closed my eyes because the room was spinning. After about ten minutes I opened my eyes and it was still spinning, so I stayed sitting and tried to wait it out. Then I got in my car and drove back to Oceanside to the VA clinic to report to my physician. She did an EKG (electrocardiogram) and had me admitted to Tri-City Hospital immediately because she said, ‘We can’t wait for you to get down to the VA hospital in La Jolla, you got to go to Tri-City right now.’ And they stabilized me at Tri-City before moving me down to the VA hospital in La Jolla and a week later I had a triple bypass. I had had a heart attack but there again, there was no pain.”

The VA now considers Charles Anderson to be 100% service-connected disabled after being rated 180% overall for various combined disabilities; Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) only pays out a maximum of 100% irrespective of how many disabilities a veteran has. Anderson’s main service-connected disabilities are 70% from the wounds he suffered in Vietnam and 10% from PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). He is sent a disability check from the VA to help pay for his living expenses.

“I was discharged in 1971 and I didn’t join my first (veterans) organization until 2016 and that was the Military Order of Purple Heart. I knew about them, but I didn’t really know what they did, and I didn’t find out until after I joined. I knew about all the other organizations and once I joined one, I started joining all the other ones. And once you get involved, you’re hooked.”

Charles Anderson is currently the commander of the 49th Chapter of the Military Order of the Purple Heart and is a former commander of the Disabled American Veterans Tri-City’s Chapter 49.

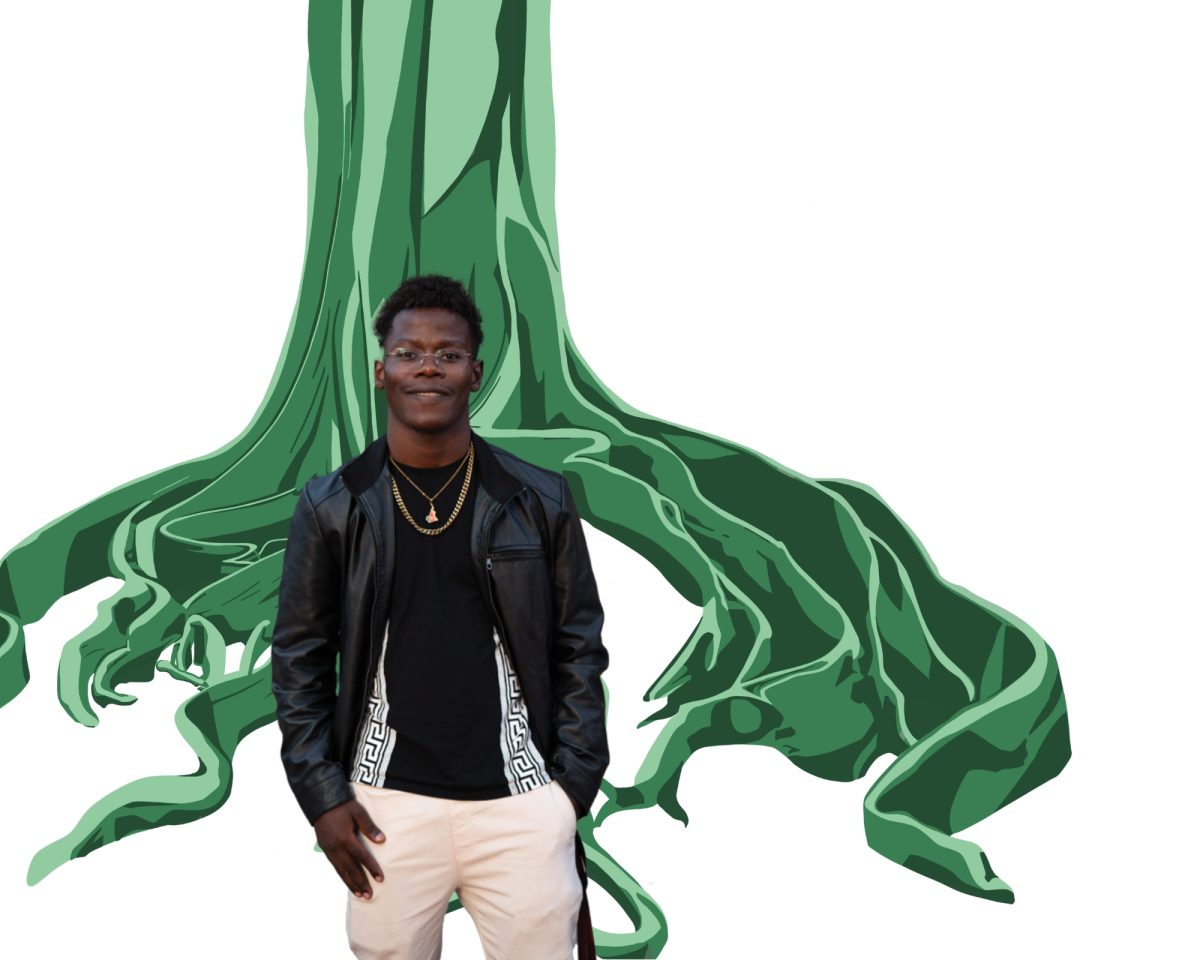

Roy Youngblood

Roy Youngblood is a native Californian and retired Navy Corpsman who served in Vietnam where he was awarded two Purple Hearts and a Silver Star. His career in the Navy began after he enlisted during his senior year of high school. He would be shipped off to boot camp three days after his high school graduation. After completing boot camp Youngblood would go on to train to become a Hospital Corpsman. The U.S Navy Hospital Corps is the most decorated rating in the entire U.S. Navy’s history.

“I became a Hospital Corpsman because the guys doing the interviews for the assignment thought that it’d be a fun name (Youngblood) for a Hospital Corpsman. From there I was sent to the Naval Air Facility in El Centro, California from San Diego where I met my future wife before coming back to San Diego. Then my duty station after El Centro was at Camp Pendleton for combat medical training and then getting assigned to 3rd Battalion 5th Marines India company.”

The Field Medical School located in Camp Pendleton is where Navy Corpsmen attend in order to learn combat medicine and train to join the Fleet Marine Force (FMF). Becoming a part of the FMF places Corpsmen in the field with Marines to provide medical care in the event a Marine is injured. FMF Corpsmen are crucial in keeping Marines alive when they are wounded in combat and before they can be transported to a hospital.

“When we were on the way over to Vietnam on the ship, I was transferred over to Mike company, so I went into Vietnam as part of Mike company. We went on a Climatization Operation where we weren’t expected to see any contact. They just wanted to get us used to the weather and the stress of going up and down hills and being in the jungle, and as soon as that was over, we were sent on Operation Hastings.”

Operation Hastings saw the Marines take heavy casualties with close to 500 wounded and 126 killed in action (KIA), including many Navy Corpsmen. During the ensuing battle that lasted almost a month, Roy Youngblood would receive a wound that earned him his first Purple Heart.

“We came in contact with a regiment-sized North Vietnamese Army force and took a bunch of casualties. We were on one patrol and the point man, the guy up front, got shot and so doing my job I went running up to take care of him before stopping. I thought to myself ‘Gee this is stupid, he walked across this wide-open area and got shot and here I am running across it.’ So, I got down and belly crawled up to him and I found that he was already deceased, and I put my head up to tell the Marines that were there that he was gone and next thing I know I’m waking up from getting knocked out cold.” On this day, Youngblood was shot in the head and earned his first Purple Heart.

“I looked down at my helmet with a hole in it and began thinking, ‘Oh boy this is a problem.’ And so, I started wiggling my fingers and wiggling my toes, then moving my arms and legs and thinking about my fiancé. I thought about everything I could think about her, where she lived, her phone number, anything like that. I could think of everything I tried to so I figured it couldn’t be that bad. My lieutenant saw that I was moving so he called out, ‘Are you okay Doc?’ and I yelled back, ‘Well I think so.’ And he called back and asked, ‘Can you crawl back over here?’ And I told him I could, so he had the Marines lay down a base of fire over my head to keep the North Vietnamese down and I crawled back to them.”

After telling everyone that he was okay and was good to keep moving, Youngblood and his unit carried on with their mission. He still owns the helmet he was wearing that day and once showed it to one of the former Commander of the Field Medical School. There is still a hole in the front of the helmet where an enemy’s bullet nearly found its mark. Youngblood claims that he’s had worse bumps on his head from when he was a kid.

Youngblood’s former company, India company unfortunately had all of their Corpsmen either wounded or killed. Due to India company losing all of its corpsmen, Youngblood answered the call to help them in whatever way he could before they were all taken off the front line. He would have to go back into the fighting after helping India Company until Operation Hastings reached its conclusion. The Department of Defense considered the operation a success.

Following the operation’s conclusion on July 25th, Youngblood joined his fellow Marines that were wounded in an award ceremony. A Marine Corps General gave out the Purple Heart medals to those who earned it. Roy Youngblood was wearing his damaged helmet at the ceremony.

“In a picture of him pinning the medal on me, I’m wearing the helmet. He said to me, ‘I bet you don’t want to get another one of these.’ And I said, ‘Well if another one came as easy as this one, I’d be happy to, because then it’d get me closer to getting me home,’ and then the general moved on to the next guy,” apparently not finding Youngblood’s comment amusing.

A few months later, on December 1966 Youngblood was sent to 2nd Battalion 5th Marines so that they would have someone who had seen combat in the unit as they rotated out some of their men. He served in Hotel company for another couple of months before the battalion asked for volunteers to join the Combined Action Platoon. The Combined Action Platoon would be sent to a village to live with the locals, and as Roy puts it, “win the hearts and minds.”

“We were guarding a bridge one day or week or so when the Viet Cong came into the village and killed the village’s chief and his family as a warning to the others not to help the Americans. So, they knew how to win the hearts and minds of the people, with terror.”

Youngblood would later move on to join another unit in one of their patrols where he would earn his second Purple Heart and a Silver Star. The Silver Star is the third highest kind of accommodation a member of the military can be awarded for gallantry in battle.

“We had gone on a patrol when one of the PFs (South Vietnamese Popular Forces) got wounded along with our patrol leader, so I went out to take care of them. The PF just had a flesh wound in the leg, so I told his buddies to get him back to safety after I put a battle dressing on him. Then I got over to the patrol leader and he was hit a little more seriously, so I fixed him up. I said to him, ‘We can stay down here in their targeting area in the rice patties, or we could get on the dike and run a lot faster. We’d be a bigger target but for a shorter time.’ And he said, ‘Let’s get up and run.’ So, I helped him up and we took off running and we were a few yards away from cover and my leg went out from underneath me all of a sudden.”

After being shot in the leg, Youngblood had to crawl the remaining way to get to cover before getting on the radio and calling for help. Within minutes his unit and their partner force had helicopters circling above their position and were evacuated to a hospital in Da Nang, Charlie-Med. At the time Youngblood had no idea that his actions of providing care and saving two of his men would get him awarded the Silver Star.

While being treated at Charlie-Med in Da Nang, Youngblood’s doctor recommended that he get sent back to the U.S. for more extensive care and treatment. This conflicted with his plan to re–enlist in the Navy while in Vietnam so that he could get his “shipping over” bonus tax-free. His doctor asked him why he needed to do that, and he told the doctor, “Well when I get back to the states, I’m going to get married and figured I’d need a little extra money to be able to afford that.” His doctor then told Youngblood’s Commanding Officer (CO) that he was fit for full duty and could re–enlist immediately without requiring further care. The next day his CO came to the hospital and had him re–enlist while still in Charlie-Med. He was then congratulated for re-enlisting in the Navy for another six years. His doctor then told the nurse that his leg still needed treatment and sent him back to the U.S. for further treatment and rehabilitation.

Roy Youngblood would go on to marry his fiancé after returning home from Vietnam. He left the Navy and attended Mira Costa Community College, got his Associate of Arts degree, then went to San Diego State University and got his Bachelor of Arts degree. He would then go on to enroll in SDSU’s teaching program and earned his credentials, going on to work as a substitute teacher for 21 years and teaching a variety of subjects.

Roy Youngblood and his wife have two daughters, six grandchildren, and three great–grandchildren. He and his wife currently enjoy spending their time going on cruises and plan on going on a cruise to the Mexican Riviera this Veteran’s Day weekend.