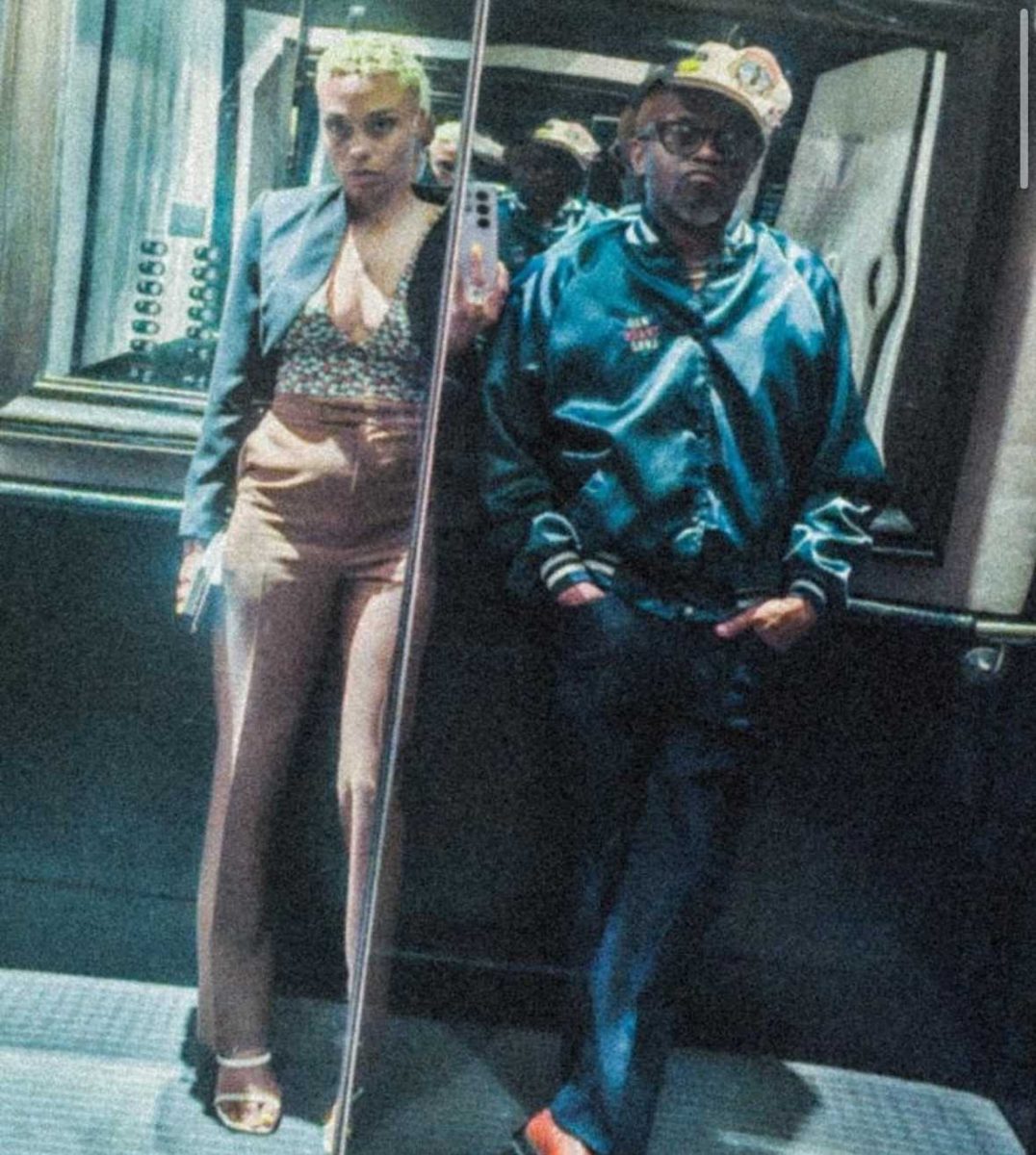

Palomar Multicultural Professor Jerry Rafiki Jenkins woke up to the etchings of a swastika and symbols of SS bolts, a Neo-nazi symbol for Schutzstaffel agents, and SWP, a slogan for supreme white power, on the wet concrete of columns guarding his homes front steps in Mira Mesa on Sept 9.

Jenkins home was in the middle of a remodel during the incident when construction workers notified him and his wife Katie Sciurba, a professor in the English department of San Diego State University, of the incident.

“My stomach sank as soon as I saw what the images actually were, what the insignia was,” Sciurba said.

Sciruba’s first thoughts were on the safety of her two sons, a five and 15 year old, and who in her neighborhood could’ve done the etchings.

Jenkin’s thoughts were directed toward the physical need to protect his family.

“I called some friends I was like, ‘we need to get some protection, we gonna go hunting;” that was my first response,” Jenkins said. “I was ready to kick some ass.”

Sgt. Lisa McKean of the San Diego Police Department’s Media Services Unit said that the vandalism at Jenkins home was the first for the year within that area within the cities limit she’s heard of.

“It’s scary,” Sciurba said of the incident. “It’s scary because we live in a very diverse neighborhood and both of the children, (and those in the neighborhood) that I see are mixed. “

Sciurba said that she felt safe in her neighborhood because of the fact that there was a diverse group of families in the area and reflected her biracial family, but the incident led her to question her family’s safety and increase their homes security.

“That’s my phone,” Jenkins said as his phone continuously went off during our interview. “We got this in light of the vandalism so it’s like this little thing that allows us to see who’s coming up to the door and all that.”

The white supremacist markings were reported as an act of mischievous or malicious vandalism rather than a hate crime, McKean said

“Swastikas don’t constitute in of itself a hate crime,” McKean said.

For it to be considered a hate crime, McKean said there would have to be more intent other than simply wording or lettering. However, Sciurba and the people of her community believed it was a hate crime and defined it that way, “for the symbols alone.”

“Were they trying to instill fear in us because of what we represent, because of what our kids look like, what my husband looks like or was it people who did it as a sign of opportunity, for example teenagers just seeing wet cement and put there to get people angry then I think that’s a bit different,” Sciurba said. “They chose those symbols for a reason, which I think is very telling.”

The family has lived in Mira Mesa for more than six years and had moved from Vista after an incident that happened outside the couple’s bedroom window between individuals with tattoos depicting swastikas on their arms.

“We were asleep at around 12, one in the morning (and) somebody’s running around the corner (shouting) ‘beat his ass like you beat a nigga’,” Jenkins said. “So, I’m grabbing my protection and walked outside and literally you could hear the pounding of somebody’s flesh; you could hear the punches at least a block away.”

The family left the etchings on their columns for more than a week to gather evidence, let the cement dry and to use the experience as a teaching moment for their sons, Jenkins said.

Sciurba said that her five-year-old son told her that they were, “just letters mommy.” She wanted to make sure he knew what the symbols meant, regardless of the vandals, and to be aware.

Photo by Katie Sciurba