The hot July air was just settling in as school teacher Sarah Davis started her summer vacation in earnest—the stress of the school year slowly melting away like a popsicle in warm weather. Accustomed to the yearly rhythm, to Sarah it seemed like a usual day of post-year freedom, full of idyllic peace and relaxation… until it wasn’t.

“I woke up that morning feeling slightly nauseous. It was pretty normal after the end-of-year stress. I didn’t think much of it. I certainly wasn’t going to let it ruin my plans for the day,” said Davis. “My husband and I were all set and ready to go on a hike. It was the big start to our summer adventures.”

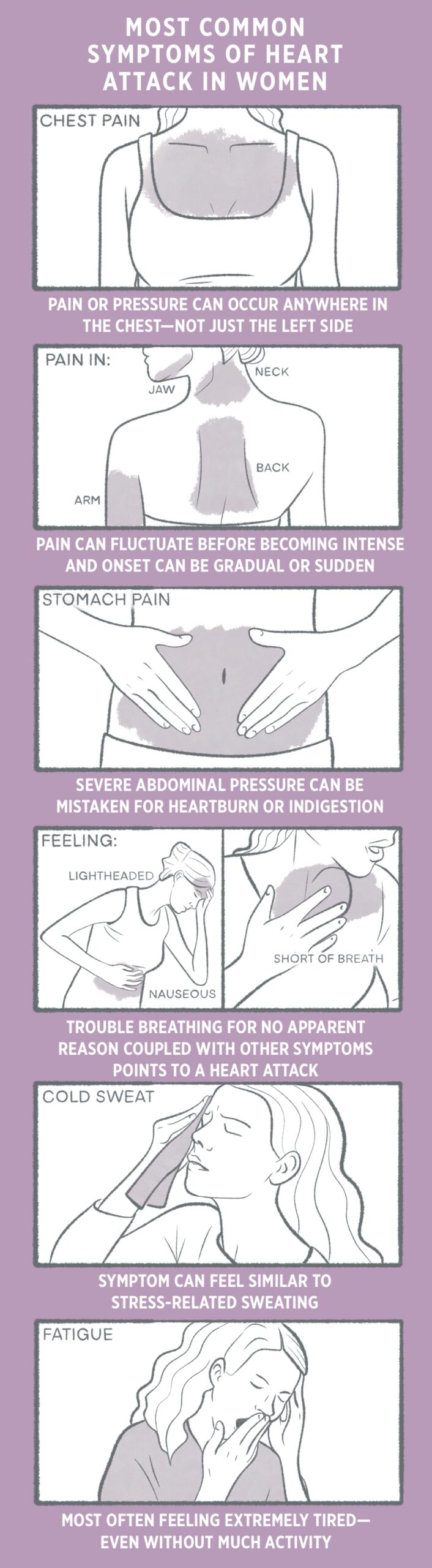

As they began their trek, she felt fatigued more rapidly than normal, paired with shortness of breath, abdominal pain, and tension between her shoulders. “I really wanted to press on but my husband could tell just by looking at me something was wrong. If he hadn’t been so adamant that day that we turn around, I probably wouldn’t be here,” Davis recounted.

The symptoms she experienced that day seemed innocuous enough but ultimately landed her in the hospital for four days—Sarah Davis had suffered a heart attack.

“I consider myself so lucky to have a partner that knows me and what’s not normal. He really advocated for me and pushed for more tests when I wasn’t able to. I had no idea what was happening to me,” said Davis. “All I knew about heart attacks came from medical dramas on TV where a guy clutches his chest and keels over in pain. I never would have guessed the symptoms for women were so different.”

Davis isn’t the only one. Women experiencing a heart attack often don’t realize it because the symptoms can be explained by other common ailments like the flu. The variance in women’s symptoms also leads doctors to misdiagnose heart attacks at a higher rate than their male counterparts.

A study in the Journal of the American Heart Association found that women presenting with chest pain wait 11 minutes longer than men to get care in the emergency room.

Additionally, women are less likely to undergo cardiac testing, and once diagnosed, they are less likely to be prescribed guideline-recommended medications. Cardiovascular disease is the number one killer of women worldwide, but women only accounted for 38% of all trial participants between 2010 and 2017 according to the American Heart Association.

Heart disease is only one area where women’s symptoms are less publicized or even outright unknown. Sleep apnea, stroke, ADHD, and autism are just some of the conditions where the commonly known “textbook” symptoms apply mostly to men, while women present differently.

Efforts to bring about change in how women’s healthcare is viewed surged starting in the 1960s and came to a major turning point in the 1980s after a 1977 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) policy recommended excluding women with childbearing potential from early-phase drug trials. In 1982, The Physicians’ Health Study, a clinical study detailing the effects of Aspirin on cardiovascular health, was conducted with 22,000 male participants and no females.

After much outcry and advocacy, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) released a memorandum in 1989 that encouraged researchers to include women and minorities in studies. If those groups were excluded, scientists should include a rationale.

Strides have been made over the past 30 years to further rectify the disparity. The previous memorandum became law in 1993, requiring all NIH-funded research to include women and minorities in clinical trials. In 2016, NIH implemented a policy that requires preclinical research to consider sex as an important biological variable in both human and vertebrate animal studies.

However, many drugs approved by the FDA before 1993, with little to no testing on women in clinical trials, are still being prescribed to men and women at the same dosage. Findings on the popular sedative Ambien show why using the same dosage can be problematic with women needing just half the dosage of men to safely take the drug.

“Research on women’s health has been underfunded for decades, and many conditions that mostly or only affect women, or affect women differently, have received little to no attention,” said First Lady Jill Biden when announcing a new White House initiative on women’s

health research.

“Because of these gaps, we know far too little about how to manage and treat conditions like endometriosis and autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis. These gaps are even greater for communities that have historically been excluded from research – including women of color and women with disabilities,” Biden added.

Filling the gaps will take time and money.

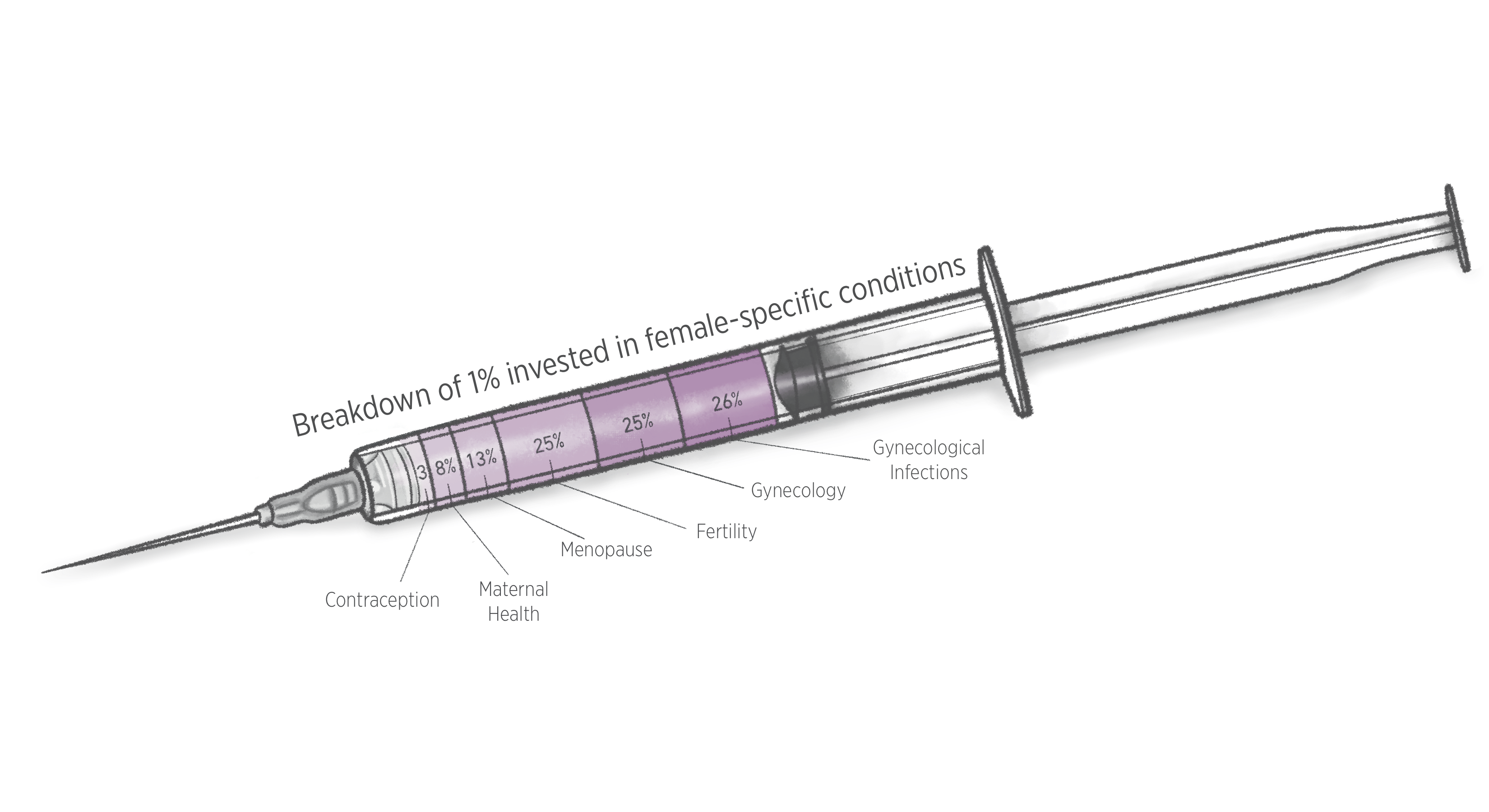

In 2020, data showed that only approximately 1% of the $198 billion of healthcare research and innovation was invested in female-specific conditions beyond oncology.

According to an article in the Journal of Women’s Health, NIH allocates funds more heavily to issues that affect men’s health than it does those that affect women’s health. The study cited that funding for prostate cancer ranked first while the gynecological cancers: ovarian, cervical, and uterine, ranked 10th, 12th and 14th, respectively.

Liliana Rosales, a college student in Nevada, had to take a leave of absence from school when she started to experience sudden weight gain and irregular menstruation along with high levels of fatigue.

“It was worrisome at first, of course you wonder why is this happening and such, and then it got embarrassing too,” said Rosales of her increasing symptoms. “I had a mustache, hairs on my chin, bad acne. I didn’t want to be seen. You know? I developed depression. Even so, doctors didn’t take me seriously.”

After seeing four doctors who could not diagnose or advise other than lose weight, she took to the internet to find answers but discovered others with similar symptoms and experiences. They all had either been diagnosed with, or highly suspected they had, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS).

“I cried that night. I felt so alone before, but there were so many others out there just like me. It was a relief to feel validated and have a name to put to what I was experiencing,” said Rosales. “I felt empowered to try a new doctor and ask for tests that ultimately led to a diagnosis.”

The diagnosis was only the start of a lifelong battle. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), PCOS affects 6% to 12% of US women. While it is one of the most common causes of female infertility, it was so underfunded that it didn’t appear as a line item on the NIH list of medical conditions that receive federal support until 2022.

While it is hard to quantify private industry spending, there is a lack of FDA-approved polycystic ovarian syndrome treatments, likely reflecting the lack of investments from drugmakers. Most medications used to treat the symptoms of PCOS are off-label prescriptions—drugs technically approved for other conditions.

For a fairly common condition discovered nearly a century ago, current research is lacking and treatment options are sparse. New research will take time and resources.

“I have a name for the dragon I’m fighting now but the battle will be long,” said Rosales. “At least I’m not alone. I hope more doctors take it seriously for research and things. We deserve better options.”

Women’s reproductive health issues that are lacking in research, such as PCOS and endometriosis, can adversely affect both physical and mental health. In general, women experience depression at a higher rate. According to a 2018 CDC study, women were twice as likely to have had depression than men.

Additionally, women have a tendency to be overlooked in the diagnosis of mental health issues like ADHD and autism since they were traditionally considered to be “male disorders.”

The rate of women being diagnosed with either condition later in life has been on the rise in recent years. New statistics show that women are often undiagnosed or misdiagnosed due to their varying symptoms. Similar to physical illnesses, symptoms of mental health disorders in women are not “textbook” and can often be mistaken for symptoms of other issues.

“I was really young when I was diagnosed with anxiety. Two years later they said I had an eating disorder. Every day felt like this insurmountable struggle just to behave normal,” said Jamie Grosh, an autistic woman. “It wasn’t until I was much older that a doctor suggested I might be on the spectrum, and even older when I finally got an autism diagnosis.”

For Grosh, the diagnosis felt as if it came too late. “I have help now, which is great, but I had already learned to manage it. I really needed that help when I was younger and didn’t know what the hell was going on,” Grosh said.

Even as an adult, getting a diagnosis can be hard. Only recently has an MIT study shown that the criteria and threshold of a commonly used screening test filter out a much higher percentage of women than men. Autism studies also enroll a consistently smaller number of female subjects or none at all, making it increasingly difficult to develop accurate diagnosis criteria.

Similarly, the estimated age for males to be diagnosed with ADHD is seven, while for females that age jumps to late 30’s to early 40’s. A 2020 study showed that in childhood, the boy-to-girl ratio for ADHD diagnosis was about 3-to-1, and in adulthood that ratio evened out to about 1-to-1. The findings suggest that girls are frequently underdiagnosed in childhood.

The research informing diagnostic criteria suffers from a gender bias due to being developed primarily on behavioral presentation in males. A prior study found that the 70 empirical studies on ADHD published in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology between 1987 (the year it was formally titled ADHD) and 1994 had 81% of participants being male and only 19% female.

For general medical and mental conditions, as well as women-centric issues, the gaps must be filled in women’s healthcare. Heart attack survivor Sarah Davis beat the odds herself but noted that the gaps remain a daily danger for women.

“Too often we get our health through the male lens. It’s just the way it is. We have to be aware of it,” said Davis. “But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t strive for change.”