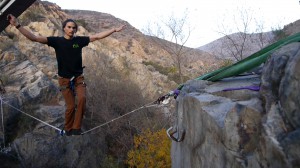

Fifty feet above the ground, 100 feet to walk and only an inch of wiggle room.

As I stood on the edge of the cliff I looked at the ground below that is covered in rocks, trees and bushes with spiky leaves. I probably wouldn’t die if I fell but it would certainly hurt.

Thankfully, I was wearing a harness tied to a leash that was connected to a line that reached the other side of the canyon. It seemed like miles away, with many variables that could potentially go wrong.

I was in Otay Lake County Park in East San Diego with a group of friends. One was experienced highliner Gene Bordson, who set the line up, and another was Lane Masar, who is on a professional team.

We hiked far off any seemingly designated trail to a canyon surrounded by a desert landscape.

I sat on the one-inch webbing line and slid my body across. It burned and felt like a razor slicing my thighs and hands open. Most slacklines are made from nylon or polyester material, which gives it its dynamic and “stretchy” movement.

On this particular day, the first time I had ever been that high in the air with my bare feet dangling, the tension created by the webbing morphed the material into an unbearable substance.

This line felt extra knife-like because it was two lines on top of one another for double protection. In case one line ripped, there would be a back-up. Safety first, comfort last.

I inched away from the nearby tree and the cliff so that in case I stood up and fell I wouldn’t go swinging into either. I had to crawl on the line a few feet out so I would be safe.

Once I was out of the danger zone, I placed my barefoot on the line and tried to stand up. The wiggling of the line would not stop and it was next to impossible to get the momentum to get my body up.

When I got the nerve to actually attempt a full standing position, I fell off the line, plunging into the air. I was caught by the three-foot leash and did not fall into the canyon below.

It took all the strength in me to get myself back on the line after falling. The leash was swinging in the wind and my arms could not reach the line so I had to wrap my leg around the leash to create a chair in mid-air. I swung my body over the line after gaining momentum to jump and grab hold.

Heart racing and muscles exhausted, I crawled my way back to the cliff.

“Maybe another day I will be able to stand up,” I thought to myself.

To walk across a highline is a fear-facing sport. There are risks, but trusting the gear and equipment is key.

Walking across a slackline is difficult to do even when only a foot off the ground. The key basics to remember and build upon are to stay centered with gravity by finding a focus point to keep your eyes on. The initial movement of standing up can throw someone into the ground so it is essential to keep your arms up, just like a monkey does when traveling across the trees.

What makes slacklining different than a tightrope is that a slackline moves like a trampoline and you have to ride it almost like a wave in the ocean. Fighting the sway doesn’t work. You have to move and bounce with the motion of the line and accept the fact that you have no control, accept to be at the mercy of it.

The art of slacklining has created a subculture of its own, slacklife, bringing people together in a community, while challenging your body to overcome fear and balance.

“So far the slacklife has given me a chance to form new lifetime friendships with some amazing people living their very own slacklife. The slacklife is starting to web the world,” Masar said.