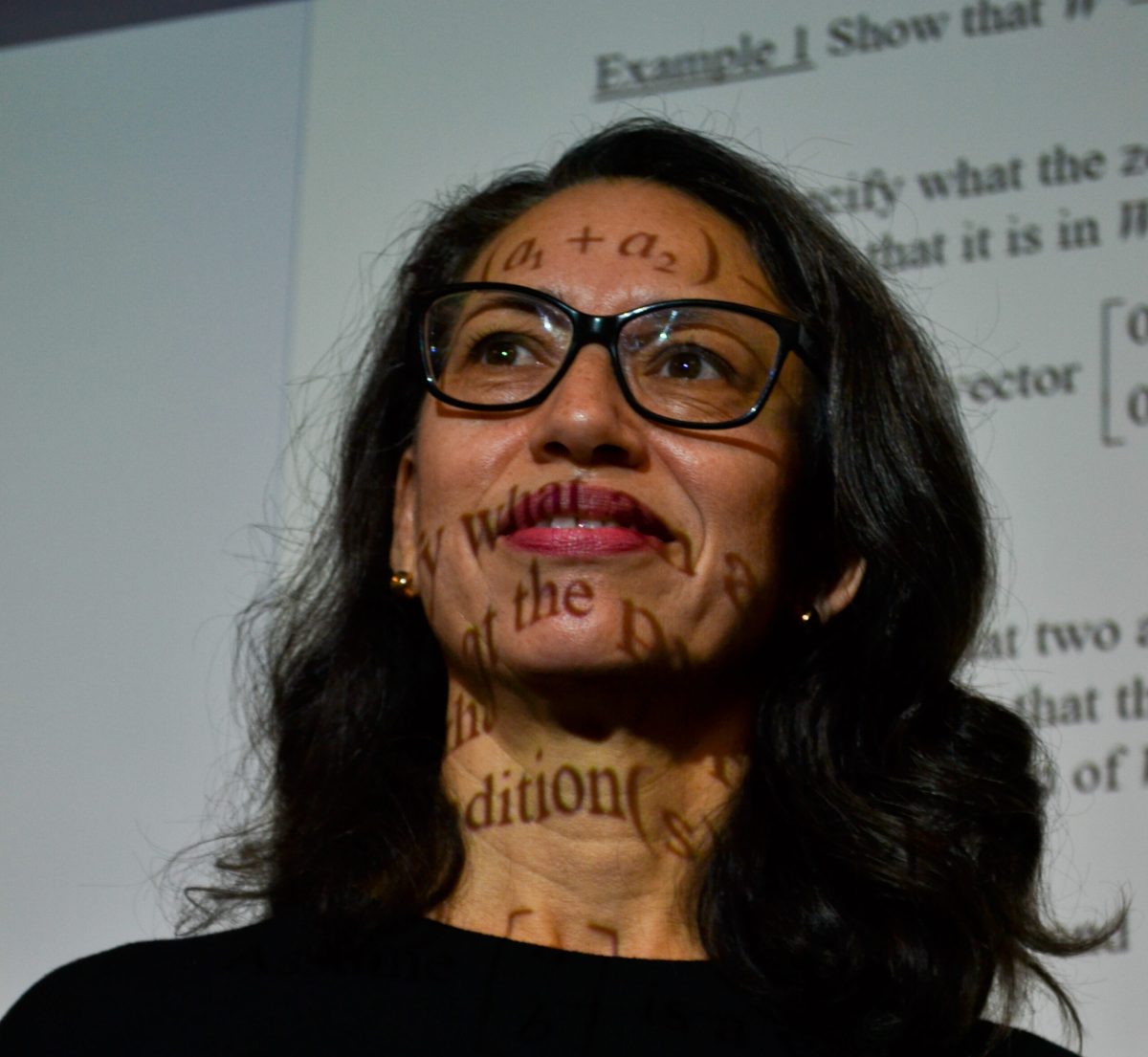

Throughout her personal life and her career at Palomar College, math professor Martha Martinez has been the first on many occasions. Born in Michoacan, Mexico, as the seventh child and the youngest daughter in her family, she lived there for 17 years before moving to the U.S. as a senior in high school.

She began taking English Language Development classes at Palomar. After three years, she transferred to Cal State San Marcos where she obtained her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mathematics. She returned to Palomar and got a full-time job as an instructor in 1996.

“As a Latina, I value being close to my family, so lots of tios, tias, and cousins. I come from a big family of eight siblings, and six of them were living here in Escondido when I came, and I wanted to stay as close as possible to my parents and my siblings,” Martinez said.

When she first arrived in the U.S., her English was limited. She felt completely lost in her civics and history classes but understood the concepts that were being covered in her math classes. “I think it was Venn diagrams, and I was like, ‘I know that.’ So even though I didn’t know the language, I knew the math that we were covering. So that kept me going in that direction. Even though my English skills were limited, I stayed with math.”

Many students that pass through Palomar are first-generation students, especially amongst Latino students. After Martinez became the first person in her family to graduate college, she was hired at Palomar as a math instructor, where she was the first and only Latina in the math department.

Martinez was also the first ever professor to teach a bilingual math course at Palomar more than 15 years ago. She said, “I was speaking in Spanish most of the time, I was also introducing the vocabulary in English just so that they could recognize it once they moved on to the next class. That class was awesome because my students were able to practice their Spanish, and they were able to relate and to have a nice social group, a little support group that they could rely on when they needed help, and It was one of my best classes.’’

According to Palomar’s 2022 Institutional Self-Evaluation review, 32 percent of students identify as Hispanic, but only 12.8 percent of the full-time faculty are Hispanic.

“The Mathematics Department is probably the largest department of Palomar, and for a while, I was the only Latina, so I felt like an outsider. I was not able to relate to other people in the department as well as, you know, if I had more Latino colleagues to talk to,” she said. “We are a very large department, and it’s kind of interesting that we’re not very reflective of our student population. We have almost half of our students being Latinos.”

One of her colleagues since 2016, math professor Luis Guerrero said, “She’s involved in everything. She’s done a lot of work for ALASS and for Tarde de Familia and many other projects. 2-3 years ago, actually, when the catalog of the school was still printed and sent out to students. She appeared with one of her students on the cover, and I think that really shows her devotion to her students and wanting to help them and show them the help they need,” he said. “We need to clone her so there’s more people like her in our department.”

Being the only other Hispanic math professor at Palomar, in Spanish, Guerrero stated in a telephone interview, “Palomar is a Hispanic serving institution, and 47 to 49 percent of students every semester are Latino, and all students need to take one or two math courses in order to get their diploma. So representation is super important. Palomar needs to invest more in hiring more Latino professors in STEM in general.”

He adds, “They could make more posters in Spanish and introduce more Hispanic icons in the sciences so that students can see that they can do it as well, and so they can see themselves reflected in high positions and with advanced titles rather than just technical careers.”

A 2021 study in the Journal of Adolescence cites that “Latinx students are underrepresented in higher-level science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) coursework, in high STEM achievement test scores and in STEM credentials earned and, only 7% of Latinx individuals are employed in STEM fields. These low numbers demarcate future individual and societal costs, such as reduced career opportunities and future earnings.”

They also cited that “Latinx youth experience systemic barriers in their educational trajectories, including ethnic-racial discrimination and prejudicial social rhetoric.”

When asked about the challenges that her Latinos students face at Palomar and what she does to help them, Martinez said, “With my Latino students more often than with the rest of the students I know that they need the extra support. So I think it’s a cultural thing, but ‘also an age thing. And I think the only way that gets resolved is with time and experience. And then being able to see themselves reflected on their faculty, and I get that’s a big problem because we don’t have enough Latinos.”

One of her Latino students is Genaro Salazar, a tutor at the math center. In an interview, he said, “When I was struggling understanding the abstract concepts in Linear algebra, she was there to calm me down and reassure me that studying and reviewing can only help me persevere in the tougher courses. She is a very reassuring person, and I really respect that,” he said.“She is always open to help others and lend a hand in people’s situations.”

The biggest challenge today, not only for students but the entire math department, is the introduction of the state law AB 1705 that prevents students from being taught remedial math courses.

“So we used to be able to teach pre-algebra, beginning algebra, intermediate algebra, and then college algebra. So most of our students coming out of high school, unfortunately, were placed into pre-algebra. And they had to take all these math classes to get to the transfer-level math classes that they needed.” she added. “But because we no longer offer those lower-level classes, everybody has to start at the transfer level. And most of them are not ready.” Martinez said.

This means that for math professors, every semester is more challenging to teach at a level where 90 percent of students aren’t prepared. Although there are some solutions to work around, like counselors overwriting the math requirements to take statistics and quantitative reasoning for non-STEM majors, students are still simply overwhelmed. Martinez said, “Many of our students don’t hear that message from their counselors or even from us. It just doesn’t register until they’re halfway through the semester and they’re failing.”

Martinez is involved in the Association of Latinos and Allies for Student Success (ALASS), one of the only groups at the Palomar campus dedicated to helping students succeed by holding events for not only students but also their parents. They work to create initiatives that can help support Latino students.

To the students that are struggling and need help, Martinez advises, “Ask tons of questions, get help, don’t be afraid to reach out and grab the hand of that person who’s been willing to help you all along and it’s always there for you.” •