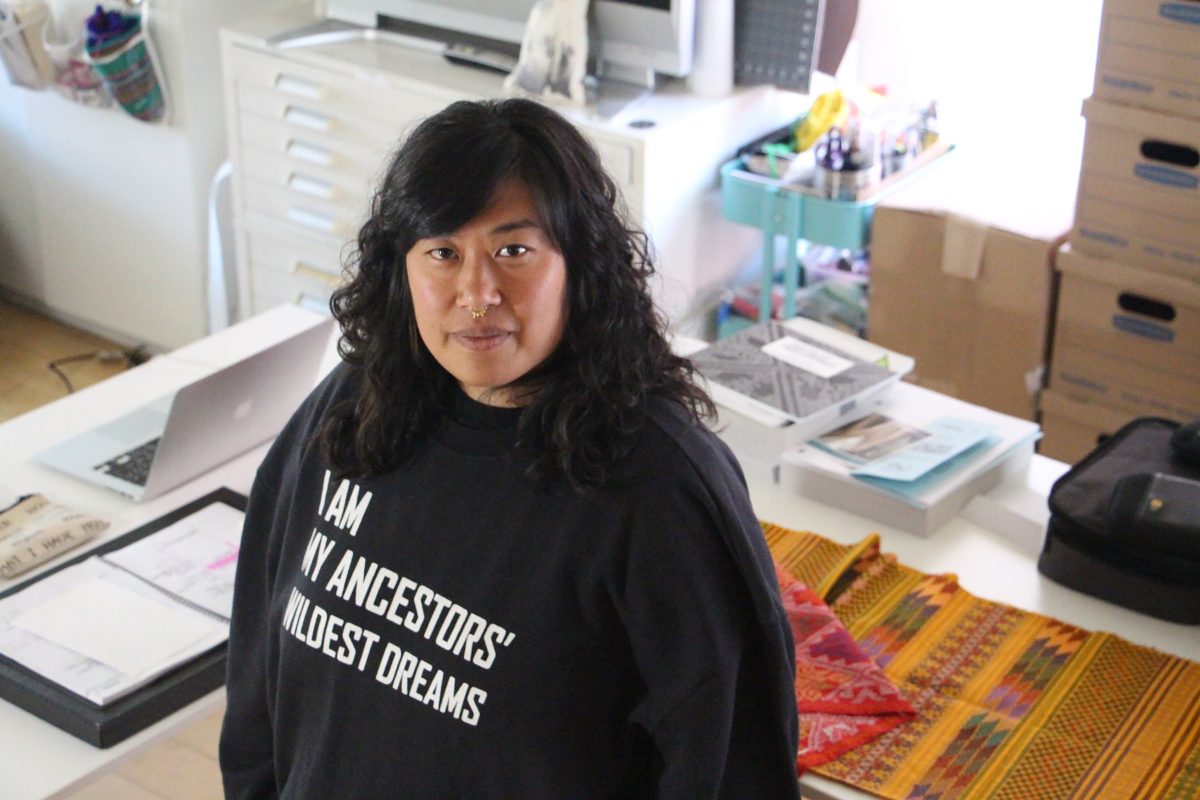

Her art uncovers layers of heritage and cultural disconnection and she’s using it to carve out a new path for those who feel marginalized and underrepresented.

Stepping into the home of Rizzhel Javier you’re immediately assured you’re in the presence of a friend. Her home reflects her laid-back style and demeanor. Things aren’t arranged in any particular place, but the space serves a purpose beyond image. It’s a multi-utilized space where Javier lives and creates art from. It’s the house she grew up in, but it’s not the same home her conservative parents raised her in.

Somewhere tucked away lies an old Humboldt State University newspaper. It features Javier on the front page. She would go on to be a focus in many articles that boast her work and influence, but this article drew attention to her for an entirely different reason: her ethnicity. A topic that had long been a silent weight she carried.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of July 2018, 83.5 percent of the population in Humboldt County is Caucasian. And it wasn’t much different when Javier attended undergraduate school there. The headline alongside her picture on the front page was titled “Exotic.”

There it was in print. All of her internal feelings of not fitting in with society glaring back at her on the front page of the school paper for her and everyone else to see.

As a first generation Filipino-American growing up in San Diego, Javier felt an overwhelming disconnection between her cultural identity and what she saw depicted in her community and in the media. Television depicted families that looked nothing like her. She didn’t see herself in the history books at school. At home the discussion of Javier’s Filipino heritage was non-existent. With no space to discuss her identity she took on an identity reflected by her peers.

She recalls comments from middle school such as, “You’re so whitewashed.” “You’re the whitest Asian I know.” At the time these words turned her against her Asian identity. It was these early memories where she says she first realized, “oh, culture is a thing,” and “there are layers of culture.”

One place that made her feel right at home was art class. From elementary school through high school she excelled in her art projects. Ceramics was a big focus at the time and she developed a great skill in craft and technique.

Her pursuit in art brought her to study at Humboldt State University. Many pivotal moments would take place there. One being the newspaper headline that called out her insecurities. But more prolific, at the age of 19, she would find a lifelong friend and mentor in teacher Don Gregorio Anton. Anton exposed Javier to a new form of art expression: darkroom photography.

He came into her life and opened up a whole new meaning of the word “art.” This is when Javier began to learn that art isn’t just something that sits in a museum or hangs on a wall. In the words of Anton, “Art appears everywhere, all the time. It is in the detail of expression often overlooked, the way in which we strive to care. It is in the response of emotions we possess. Art is not exclusive, but limitations are.”

In an online article, “In The Heart Stories: Rizzhel Javier-Artist, Educator,” written by Jella Roson, Javier describes a profound memory from school. She recalls Anton assigning her to find a book with a Filipino artist and bring it to him. She found one Filipino painter online.

It gave her hope to finally see someone like her succeeding as an artist. This moment would come full circle 10 years later when she returned to Humboldt to give a lecture. She shares how a Filipino student came up to her and said, “I never thought I could do this, but meeting you made it feel more possible.” In this moment Javier knew she was on her true path. Her passion is to help others find their authentic voice and expression and use it as a means to connect.

The stories people hold matter to Javier. She knows all too well what happens when stories are lost. Growing up, the silence of her parents resulted in cultural and generational dissonance. And she’s breaking the cycle.

Her artwork pushes to create dialogue into uncovering the layers attached to identity. Through her teachings and various collaborations she creates space for people who feel like they aren’t seen or heard. Javier is healing force in her community, especially to the younger generations. She guides them to discover their own truth, showing them limitless means of personal expression.

One way she does this is through connection. She brings artists of every race and gender and upbringing into her classroom to show students the many faces of an artist. She also brings her students to various art functions where they see and experience work that goes beyond the media’s conception of what art is.

When you talk to people about Javier they immediately open up and come to life. Christina Ree, program manager of Pacific Arts Movement, expresses how lucky PAM is to have Javier working in their organization. She speaks highly of the lengths the artist will go to watch her students transform and succeed. “She’s a really special person that everyone trusts. Everything she does, she does with such commitment,” says Ree.

Ree is right. Javier has a way of transforming a classroom into a very special place. She is the teacher she needed growing up. When thinking of her students she asks herself, “What are the things we want to learn that don’t exist in normal curriculum?” She’s very aware of the politics that exist in representation and in access, and she doesn’t shy away from topics such as privilege, sexual prejudice, or invisible borders in the community. She seeks the truth, whatever that may look like for someone.

That’s where she encourages healing through art. When her students come to her saying they don’t see themselves in movies she says back to them, “Well, then let’s make it.” If they don’t have access to expensive art supplies then she helps them discover a way to express themselves with accessible, unconventional materials. Javier fights for her students. In return, she learns she must also continue fighting for herself.

At the age of 30, Javier had success in the eyes of her parents. Not due to art, but due to her financial status. She was making a good living, but something was missing. Her heritage was calling out to her, and she dropped everything to answer that call.

For the first time ever, she traveled to the Philippines. She would stay with her grandparents in the house her father grew up in. Her grandmother, (Lola in Tagalog), welcomed her visit, but only with her father’s blessing.

To her shock, the blessing did not come easy. Javier had to fight with her father. He could not understand why she would leave behind her job and gave her every reason to stay. She had to make it known that the history he worked so hard to leave behind also belonged to her.

After many tears and self doubt she took the journey and made it home to a place she had never been before. As some people in her family would call it fate, her grandfather passed during her visit in 2013. Through this difficult time she was right there, caring for her Lola, exactly where she needed to be.

Javier found comfort and connection in her trip to the Philippines and because of that she has gone back every year since in an effort to further develop and share her own story.

Lola looks forward to her granddaughter’s return this fall.