There is a saying in Japanese. Mono no aware.

The saying is not easily translatable to English. Literally, it means “the feeling of things,” and can be described as the feeling of awe. This barely scratches the surface, but the loss in translation creates so much meaning as well.

Mono no aware is far easier to explain than define, and there is no better way to do so than by describing the cyclical nature of the Japanese cherry blossom trees, also known as the sakura tree

As the cherry blossoms bloom they create a feeling of awe. In their descent they bring joy, laughter, togetherness and warmth amongst many other emotions. After the fall, the blossoms are at their aesthetic precipice, they exist in a state between life and death and create a new landscape as the beautiful, yet decaying petals blanket the ground.

The branches of the sakura trees, devoid of blossoms, stand as a stark reminder of the ever-changing essence of life, for they will inevitably bear new buds.

But what if the cycle was not to be?

What if the branches remained bare and did not produce new flowers?

The blooming period of the sakura tree is short. This is akin to the cycle of students at Palomar College.

Given the nature of a community college most students at Palomar are not here for a long time before they move on to their next phase in education and in life. Even so, the graduates are replaced with incoming freshmen at the start of each school year.

It is inconceivable to think the blossoms of the sakura tree would not return each year, just as it is inconceivable to think new students would not replace those who graduate. But that is exactly what is happening at Palomar College.

Japanese student representation at Palomar College is in a free fall.

Only 33 Japanese students are enrolled at Palomar this semester, according to the campus’ Office of International Education. If trends persist, this number will continue to plummet.

Unfortunately, Palomar College and other higher education institutions don’t normally advertise themselves internationally. Instead, community colleges and universities send staff members around the world to recruit these students.

At Palomar, Yasue O’Neill oversees the recruitment efforts as the International Education Coordinator. For 30 years, her main focus has been increasing the international diversity on Palomar’s campus.

“My goal is to expand the program. Not only increasing the number of international students but increasing the number of countries that these students are coming from,” Yasue said.

International student attendance at Palomar depends not only on the hard work of Yasue, but also on whether it is feasible for prospective students to leave their native country.

The state of the country plays a huge role as well and in Japan there are several societal issues making it less likely that Japanese students will study abroad.

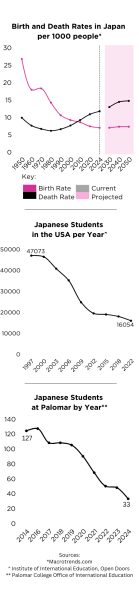

Japan had a population of over 126 million people in 2020. That number is expected to fall to 87 million by 2070 due to an increase in mortality rates and a decrease in birth rates, according to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

“Not many Japanese people and others of this generation are getting married, and they choose not to have kids. So, the younger population is decreasing while the older population is increasing in Japan,” Yasue said.

With less of the population made up of college-bound individuals, it makes sense that the number of Japanese students attending schools in the United States would also fall.

But the decrease in population is twofold when it concerns Japanese students studying internationally — with fewer college-aged individuals in Japan, there is a much better chance to be accepted by otherwise highly competitive Japanese universities.

In 1997, the United States had its highest enrollment of over 47 thousand Japanese students, according to statistics from Open Doors. In 2023, that number dropped to 16 thousand Japanese students. While it is a slight uptick from the 2021-22 school year total of 13 and a half thousand, it is still a far cry from its peak.

The decreasing numbers are not the only issue. Most of the students who choose to come to the United States to receive a higher education will attend four-year universities that can offer large scholarships over a two-year community college.

If they do not receive a scholarship to an university in the United States, Yasue explained that it’s more likely

Japanese students will study abroad in countries like the Philippines.

“Because the Japanese yen is so weak compared to the American dollar right now, it is hard for parents to support their kids through college, and these closer countries can still help them to speak English,” Yasue said.

Yasue brings up a great point that the money used in Japan, the yen, is very low in value compared to other global currencies including the US dollar.

According to Macrotrends, at the end of 2023, one dollar was worth 141 yen and in 2024, one dollar was worth nearly 152 yen. This is more than a 7% decrease in the value of the yen in less than a year.

The discrepancy in currency has an adverse effect because many Japanese students now cannot afford schools in the United States. The exchange rate is too high and many, including Palomar’s Japanese students, rely on their families to support their enrollment financially.

Ayano “Aya” Tsuda, a sophomore at Palomar College from Nagoya, Japan, is very aware of the financial difficulties associated with attending school in the United States.

“Recently, the Japanese yen is so cheap compared to US dollars. It’s hard. I am so appreciative of my parents who helped me be able to come here,” Tsuda said.

Despite having a small international student base, the Japanese students are very driven to succeed.

The average GPA among Japanese students at Palomar is above a 3.0. Outside of academics, they actively participate in school activities like sports and the student-founded Japanese Culture Club.

Many of the students who stay for two years will transfer to wellknown universities like Berkeley and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Tsuda is a student-athlete at Palomar and competes with the women’s water polo team as one of their top goal scorers. She ranked second on the team, and ninth in the entire conference this season with 39 goals scored

“First, I was going to go to MiraCosta College, but I really wanted to do swimming sports in college. But they do not have a swim team. I found Palomar College had a water polo team in the fall semester and a swim team in the winter, and so I came here,” Tsuda said.

Tsuda came to school in the United States with the goal of learning English to pursue a career with Emirate Airlines. English classes at Palomar College have greatly improved her spoken English, but she attributes much of her knowledge to participating on the water polo team.

“Thanks to the friends, the water polo girls, and the coaches, my English has so improved,” Tsuda said.

In addition to playing for the water polo team, Tsuda is also on the women’s swim team. She is the only native Japanese student-athlete at Palomar. When she graduates at the end of the semester, there will be none.

“I love the friends I’ve made and my coaches. Playing water polo for two years here has been such a precious time, and I am so sad to be done,” Tsuda said.

Hinata “Hina” Watanabe is another sophomore at Palomar College. She is from Tokyo, and is close friends with Tsuda. When Watanabe graduates she will transfer to California State University, Northridge.

“Everything that I’ve experienced at Palomar has been so amazing. A good memory I have is doing a big project with five native [English] speakers. It is difficult as an international student, but it is good for me,” Watanabe said.

With the current population and economic situation in Japan, is there really a solution to the declining number of Japanese students enrolling at Palomar? “It depends on how much resources and funding the district and school can provide us. But some things like the economic situation [in Japan] are out of our control,” Yasue said.

Before 2020, Yasue used to go on more recruitment trips to multiple countries, but COVID-19 and the current financial situation now limits her to merely a couple of these trips per year.

The change makes it difficult to recruit not only Japanese students at Palomar but also international students overall. Unlike Palomar, other community colleges like Santa Monica City College, De Anza College, and Foothill College, allot enough funds to have a whole department of international student recruiters.

This enables those other colleges to bring in several thousand international students to their campuses every year.

Yasue was recently in Vietnam and spoke with other international student coordinators from various community colleges. They were stunned that she could bring in even 33 Japanese students. Their own numbers fell as low as the single digits. Comparatively, our numbers at Palomar are good despite continuing to decrease.

Both Tsuda and Watanabe were unaware of the low presence of Japanese students on campus, and were shocked when they learned just how quickly the numbers are falling.

“I was surprised, because my friend went to Palomar as an international student. At this time, I think he said the number of Japanese students was 80. But 33 is so small,” Watanabe said.

In 2016, 127 Japanese students attended Palomar, the highest number in the past decade and is almost four times the total enrolled this semester.The entirety of Palomar’s Japanese international students can fit comfortably in a single classroom. There is a looming possibility that one day, not even a single desk at Palomar College will be occupied by a Japanese student.

Americans tend to focus on loss and disappearance in a negative way. In Japan, mono no aware and the cherry blossom trees paint a picture of all things being part of a greater cycle. One should appreciate every moment, including moments when things are lost or fading away.

There may be fewer and fewer Japanese international students attending Palomar each year, but that does not detract from the positive contributions of students like Aya Tsuda and Hina Watanabe. Their accomplishments and the memories they make here will have a lasting effect on the school and on their own futures.

Mono no aware reminds one that life, and all things in it are short and fleeting. Though the branches are devoid of blossoms now, in the future they will be full of life, beauty and vigor once more.