Cameroon, a vibrant country located in central West Africa, is filled with fascinating marvels. In its tropical forests, gorillas pick the fruit off shrubs, elephants fan themselves with their large ears, and rock pythons slither across the grassy lands. Approximately the size of California, the country is one of the most diverse in the world with over 250 cultures, languages, and tribes.

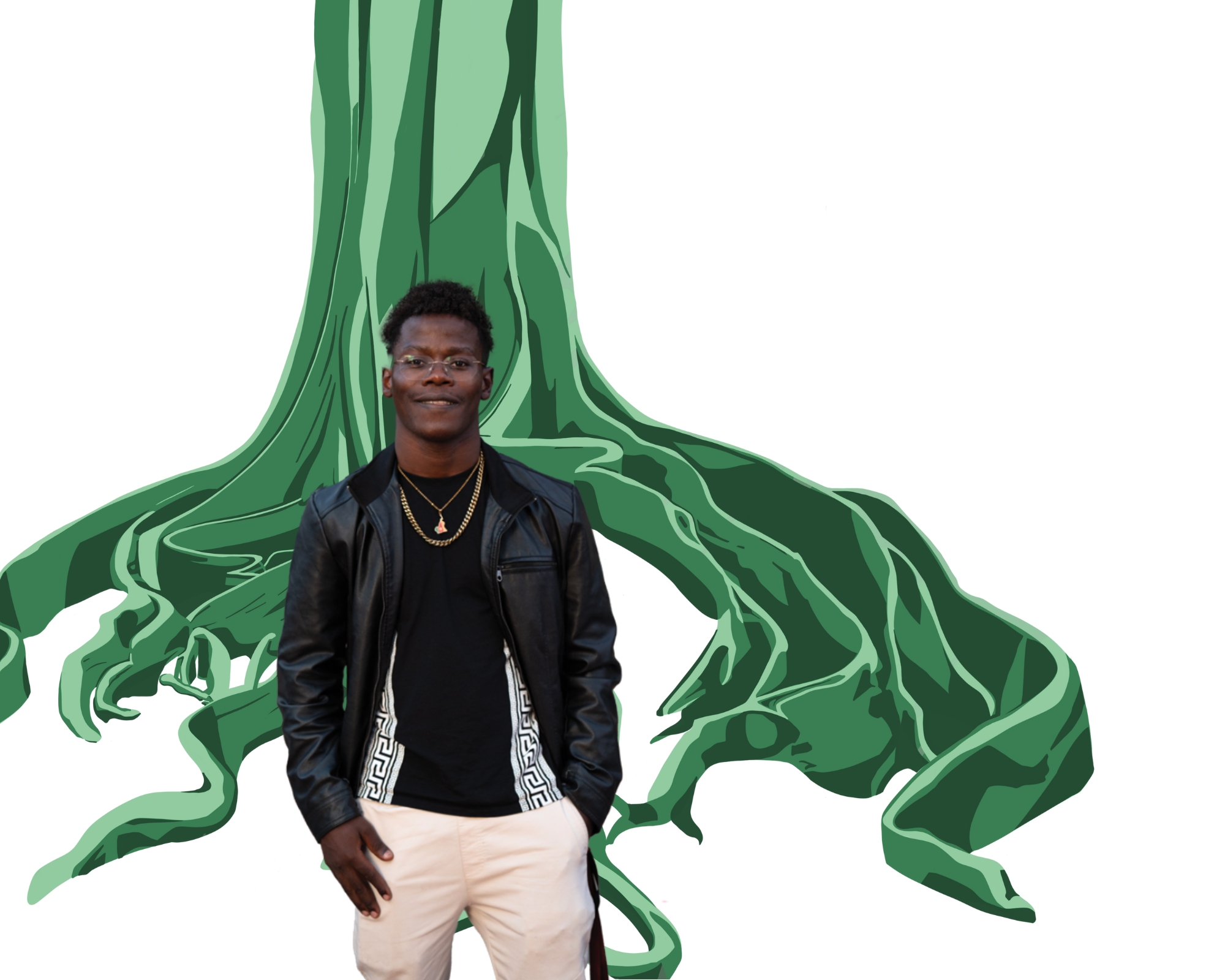

Palomar student Brightwel Ojahngoe carries the rich heritage of his roots in Cameroon where he was born to the Bakossi tribe. Though it has been years since he left his homeland, Ojahngoe vividly recalls the striking landscapes and cultural aspects that define Cameroonian life.

Cameroon is home to the Kupe Manenguba twin lakes, which the Bakossi tribe distinguishes by referring to them as female and male. Ojahngoe explains that while the female lake is the lake of life, the male lake has no life in it.

“If anything goes in there, it dies. Like, no one is allowed to swim there… Tourists have gone there to swim and all of them never came out,” Ojahngoe said.

The land is rich in oil and aluminum as Cameroon is one of the highest exporters of oil globally and the highest exporter of aluminum in central West Africa. It is also one of the highest exporters of timber.

“The trees are massive… I’ve seen a tree so big, I was scared to touch it,” he said.

The tough trunks of trees grow over 200 feet tall and, like these trees, Ojahngoe stands confident in himself and in his cultural roots.

“It’s really important to keep your culture and tradition because it creates a lineage, a lineage of witness or cultural practice, something that the kids could look back to during hard times.”

Ojahngoe now lives in California by himself, where waving palm trees poke out from behind San Diego’s city buildings. Although he enjoys experiencing American culture, Cameroonian heritage remains a major part of Ojahngoe’s identity.

“I stick to my culture so much because I know that’s who I am, and that’s where I’m gonna be, and that’s where I’m gonna leave on Earth, and that’s where my kids are gonna become,” Ojahngoe suggested.

A majority of Cameroonian tradition values family and the traits passed from one generation to the next. According to Ojahngoe, parents are responsible for their children until about the age of 30, when they become adults upon marrying and starting their own family.

“Eighteen is not really an adult. That’s still a kid,” Ojahngoe said.

When choosing a marriage partner, it is customary for marriages to be arranged in a way that focuses on a woman’s age and positive traits.

Because elders and schools teach that females age faster than males, males are encouraged to get married to a female four to five years younger. Ojahngoe explained that women must be ablebodied and healthy enough to nurture the family until her children are old enough to be on their own.

The wife is also typically younger than the husband due to economic challenges and limited education, according to a 2024 study published by the African Development Review.

It is also crucial to be mindful of who a Cameroonian chooses to have children with because the parents’ traits will be passed down to them. The mother is believed to pass traits down to her child as she carries them throughout pregnancy. Positive traits like care and ambition in a woman are influential in having a healthy family. Similarly, honesty and level-headedness in the father are important factors to pass down.

Polygamy is a common practice in Cameroon. Men get assigned multiple wives which, according to Ojahngoe, is largely out of necessity to care for the women of the tribe and have children.

Men may get married to multiple wives, however, “after the first, the second wife is not more a thing of fun, it’s a thing of necessity,” he explained. The husband creates opportunities for his wives and children by sponsoring them through school.

“The wealthier the man is in Cameroon, the more responsibility the community expects him to take,” Ojahngoe said.

Ojahngoe said that without tradition, people can feel lost and unsure about their identity, which can lead to a lack of confidence. He encourages African- Americans to go to Africa and learn about their heritage.

Programs in Africa educate African Americans about their history through the African lens, rather than the teachings of European colonizers. For instance, Ashanti African Tours hosts Ghana Heritage Tours where members of the African diaspora from around the world connect with their cultural ancestral heritage and become informed on their background.

As a member of Palomar’s Umoja Club, Ojahngoe encourages others to find their community on campus. The Umoja Club focuses on enhancing the cultural and educational experiences of African Americans and others.

“Umoja is a very inclusive space… It’s by unity,” Ojahngoe said.

The club provides students with resources, such as counseling, workshops, and tutoring, to help them succeed in college.

“African American and Black students have a place on campus where they know they belong,” Umoja Club President Kaya Quarterman said.

Umoja shares a list of 18 practices to live by, and Quarterman’s favorite is “Everybody’s Business.” This principle highlights the importance of acting as a village and including everyone to support one another.

“If you’re bothered, I’m bothered. If you’re happy, I’m happy. I share that same feeling with you,” Quarterman explained.

The rule exemplifies the club name’s direct translation—a Kiswahili word for unity. Umoja gives Palomar students a space to belong through community support.

Adrian Reyes Cabezas, another club member, has created strong friendships and connections with others.

As a person of color, Reyes Cabezas recognizes some of the same struggles Black students face and utilizes his experiences as an immigrant to become familiar with other cultures.

“I haven’t had that much connection with students of African American descent or Black students, and I think I needed that,” Reyes Cabezas said.

Born in Tijuana, Reyes Cabezas migrated to the United States with his mom in second grade. Like Ojahngoe, Reyes Cabezas recognized the importance of tradition.

“Tradition can die, but I don’t want that to happen,” Reyes Cabezas said.

Reyes Cabezas plans to pass down Mexican cultural traditions, such as Día de los Muertos, celebrated on November 1st and 2nd, to the next generation.

“The tradition is important because we don’t see death as ‘that’s it, that’s the end.’ We see it as a celebration of what someone was before and how they impacted those around us,” Reyes Cabezas said.

Día de los Muertos is a way for individuals to remember those who came before and what they did for future generations. The holiday is celebrated by setting up an ofrenda, or an altar, to honor loved ones who have passed away.

Pictures and the favorite foods of the deceased family members are displayed on the altar. Cempasúchil, the marigold flower, is used to make a path for the dead so the spirits find their way home. According to Reyes Cabezas, the dead come thirsty from the other side.

“I don’t know if this is true, but I’ve seen it. The water actually goes down after a while,” Reyes Cabezas said.

Cultural traditions allow future generations to continue flourishing by looking back on the practices of past ancestors. According to Kyle J. Clark, author of “Cultural traditions and fitness interdependence,” these are “strategies employed by ancestors and carried on by descendants, that increase the evolutionary success of the ancestors.”

For Brightwel Ojahngoe, the guidance comes in finding motivation from his African ancestors and their teachings as he strives to overcome obstacles.

“I look back at great leaders in Africa who defeated the odds… When the world told them no, they said, ‘I am gonna find a way,’ and they did,” Ojahngoe said.

Though change is presented in new environments, having cultural traditions rooting one down into familiarity can be both comforting and empowering. These traditions help build self-confidence in one’s identity, and foster a sense of belonging in a community.

“Culture, social, and symbolic capital [are] assets akin to social strength,” according to Western social scientists.

When looking at Cameroon’s vast forests, which provide homes to mixed wildlife, one can find security knowing that the immense trees that make up the vegetation are deeply implanted in a strong foundation.

“I think life is like a hike, you know…It’s one foot in front of the other and you have to worry about the next step you’re gonna take,” Ojahngoe said. “Or the current step you are taking, and don’t worry about the rest.”

Corrections: A previous version of this story incorrectly spelled a Brightwel Ojahngoe three times in the story, this has since been corrected.